Dr. Jon Hallberg on deer ticks and Lyme disease

Earlier than usual spring weather has lead to earlier appearances of ticks and earlier cases nationwide of Lyme disease. That has led to new attention on its treatment, and its signs and symptoms.

Some patients with the disease argue that doctors are not taking it seriously or treating it aggressively enough.

MPR News medical analyst Dr. Jon Hallberg spoke with All Things Considered host Tom Crann about the disease and the controversies surrounding the treatment of chronic Lyme disease.

Hallberg is a physician in family medicine at the University of Minnesota and medical director at the Mill City Clinic in Minneapolis.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

Tom Crann: Give the basic primer. What is Lyme disease?

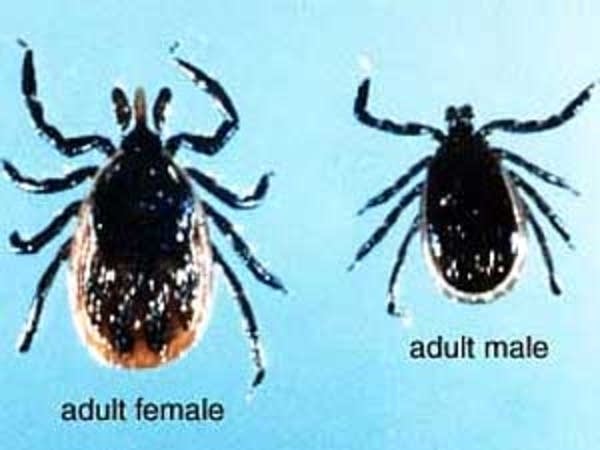

Dr. Jon Hallberg: Lyme disease is a bacterial infection that is spread through very specific kinds of ticks. We used to call them deer ticks and they're still called that, but they're now also known as black-legged ticks.

So, the bacteria live in their stomachs. The tick latches on for a meal and eventually the bacteria in its gut get into our blood stream. Under the microscope, the bacteria look a little bit like a cork screw. It has this uncanny ability to work its way into the nervous system.

What are the symptoms?

Hallberg: Most commonly, somewhere between 70 and 80 percent of the time, people get a rash. It's a classic bull's-eye rash. You get a red center, a little clearing, and then some redness around that. It's called an erythema migrans rash. When you have that, it's just very easy to diagnose.

When that doesn't happen, people (can) get rheumatologic symptoms. Their joints can feel really achy. They can have some neurologic symptoms. There's a whole host of things that can happen that are very subtle. And in fact, many of us in practice have had this experience where people have had all kinds of interesting symptoms. And it's gone undiagnosed, and then we do a Lyme test and we discover it that way.

Can it progress and become even more serious?

Hallberg: It can. Some people can get meningitis. People can have some heart problems. So it can be very serious if it's not recognized and picked up.

So, how do you treat Lyme disease?

Hallberg: Because it's a bacteria, we can use antibiotics for that. It's easier to treat than a viral illness, for example.

Are you seeing more of it in the clinic?

Hallberg: I'm in downtown Minneapolis, so I'm not seeing a lot of it. When I do see it, it's in people who have cabins up north.

[People] who've been out in the woods.

Hallberg: Exactly. They've been hiking. They've been camping. There's some reason for them to have that. I think my colleagues who work in the Hudson, Stillwater, Marine on St. Croix area are seeing a lot of it. People in Duluth are seeing a lot of it. Those are probably the major focuses of Lyme activity.

In a story today in the Washington Post, they talk about "chronic Lyme disease." They put it in quotes. Does this concept of chronic Lyme disease exist?

Hallberg: Well, the concept certainly exists. The trouble is the definition of that, and that's something that's being looked at and being worked on.

Here's the problem. (There are) people who have known disease. They had symptoms. They had a positive test for it. They carry the antibodies against the bacteria, so you can prove they've had the disease. They've gone through a course of antibiotics as they should, but then their symptoms persist. So that is a sub-set of people who have chronic Lyme disease that is still very difficult to explain and to cure.

But there is a much larger group of people out there who have not had the diagnosis made. They'll have a partially positive test. They'll have, for example, four bands, and they really need more than that to clinch the diagnosis. So they're hanging on to this idea that they had Lyme disease, that for some reason the laboratory testing wasn't accurate, their physicians aren't believing them, and they've got all these symptoms. The trouble is their symptoms are extremely wide-ranging and they simply don't meet criteria for having chronic Lyme disease, but they're looking for an answer, and that's where a lot of the controversy comes in.

What kind of symptoms are we talking about here?

Hallberg: Fatigue, fever, headache, joint aches, the list goes on. And so it's a whole host of things that can be rheumatologic, joint-based, skin-based, neurologic, and even cardiac-based. It's really difficult.

So, what concerns are you seeing and hearing about from patients like that about treatment? They want more antibiotics, right?

Hallberg: Right. The controversy is that some physicians--and the establishment would consider these folks kind of rogue physicians (because) they're sort of out there doing their own thing--would recommend long IV courses of antibiotics, potent antibiotics, for months. And that's just not accepted medical therapy.

The trouble is there are certain conditions out there, chronic Lyme disease, chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, for which we don't have easy tests. We don't have simple ways, but with advances now in molecular diagnostic testing, they're now finding that maybe people with chronic fatigue really did have a certain kind of viral illness. They're finding markers in people with fibromyalgia that actually have inflammatory markers that you can now measure. So, we're starting to kind of piece those together.

And what do we know about what's called chronic Lyme disease?

Hallberg: So far, there isn't that kind of eureka moment where we're making that link. I was just talking with an infectious disease colleague of mine today at the University (of Minnesota) who said that that's kind of the difference. There just isn't anything that kind of pops up. And you'd think now with all the advances and all the molecular studies we've got, something would pop up. And it's just not popping up. So, many of these people have other things going on, and they're just desperately seeking a diagnosis.

So, what is the latest clinical thinking on those sorts of situations? How do you treat them?

Hallberg: Well, here's what I do. I think there are many medical conditions for which we don't have a cause. I simply don't know what's causing symptoms, but rather than focusing in and getting too hung up on what the cause is, I want to treat the symptoms. I want to make people feel better. So, sometimes by taking a medication that can improve sleep, that can decrease pain, that can work in other ways, you can actually make them feel better because part of healing is actually getting a good night of sleep, not being in pain 24 hours a day.

Of course, all of these folks have gone through other batteries of tests. They've gotten second, third, fourth opinions. So it's not like they're being blown off by doctors or not being listened to. That's not the problem at all. It's just that how do you put together, cobble together a treatment plan? And that's really, really difficult.

So, what do you tell patients who say, "I want a years' worth of antibiotics because that's what this is?"

Hallberg: What's really hard in primary care is that when you have people like this who have gone to specialists, our hope, of course, is that the specialists will come up with the diagnosis, will treat them accordingly, appropriately, and they'll be better, and that's the end of it and then you continue your relationship.

But in primary care when the specialist doesn't know what to do, they come back to us. So now here you are in a small town, let's say, or in my clinic in a major metropolitan area, and people are looking to you for help and guidance and relief of suffering. And of course you feel compelled to do something, but I think most of us are uncomfortable with doing really out-of-the-box kind of treatments for fear of you don't want to be mocked by your colleagues. You feel internally that it's not the right thing to do. I don't do it because I'm worried about medical legal repercussions, but it's so different and frankly so unaccepted, most of us are not willing to take that chance.

And what is so unaccepted about that much antibiotics for that long? What's the thinking there?

Hallberg: Well, I think the thought is that for some reason this bacteria has the ability to sort of hide out. Is it sort of burrowed into joints? Is it burrowed into the brain, nervous tissue, and it's just hard to get at? It's hard to deliver the antibiotic to it, so the longer you go with a stronger antibiotic, you can eventually sort of eradicate it? That's probably the best guess because otherwise it doesn't make sense. If it's just inflammation, then ibuprofen or anti-inflammatories would take care of that. So the idea is that it's burrowed itself in to such an extent that you can't get at it easily.

But what's the caution there about doing that?

Hallberg: (With long-term, heavy duty antibiotics use), you're creating resistance. You can create diarrhea. There's a whole host of reasons why it is not a good idea to be in chronic antibiotic use, and I think resistance is very high among them. And to tell you the truth, it's cost, too. IV antibiotic therapy is extremely expensive. Of course, there are things that we do that are very expensive, but if it's unproven, that's a really tough sell.

It's now the time of year where people will be out of doors more and traveling more. For the vast majority of people who get a tick bite, what should they do?

Hallberg: It's interesting. We actually have become sort of amateur entomologists because we have to first of all know, 'Is it a deer tick?' And now the new terminology is a 'black-legged tick.' And it has to be either in its nymph phase or the adult phase, so size kind of matters.

Of course, you want to take it off. You want to get it off as soon as possible, but you should actually look to see if it's had a full meal. In other words, is its belly full of blood? And if it is, that makes a difference whether you're going to treat prophylactically or you're going to wait for a rash to appear before you treat it.

So if you've been out and you find you've been bitten by a tick, can you nip it in the bud?

Hallberg: You can, but just under very specific circumstances.

So first of all, you have to be in an area where at least 20 percent of the ticks carry the bacteria. It's a good point to know that not all these ticks are carrying the germ in their gut. Places like Minnesota and Wisconsin, though, that's a pretty good bet.

Then the tick has to actually be on you for about 36 hours. Any shorter time than that, it really hasn't had time to give you the bacteria. So it has to latch on for a while. And then you have to look and see if it's had a meal. Its belly will be kind of distended. You can see that it's full of blood. So these are all signs that you've probably got a good chance of getting Lyme disease.

And then you can also get on antibiotics if you get them within three days of taking the tick off. So if you fit all of those criteria, you can take a single tablet of doxycycline, for most adults anyway, and that will probably stop it from causing a serious infection.

(Interview edited by MPR News reporter Madeleine Baran.)