Challenges lie ahead in child pornography lawsuits

St. Paul attorney Jeff Anderson filed a lawsuit on behalf of a child pornography victim Wednesday in what he promised would be the first of many lawsuits aimed at going after those who distribute and view sexually explicit images of children.

The lawsuit filed in federal court against a former St. Paul teacher and dozens of unnamed people who downloaded pictures of the 9-year-old appears to be the first attempt in Minnesota to seek compensation for the victim through civil litigation.

Nationally, such lawsuits are rare, and their success hasn't been fully tested in the courts. But victim advocates are watching closely to see if Anderson's strategy to find, expose and sue those who view and distribute images works.

"This is a practice that's very much in its infancy," said Ernie Allen, president and CEO of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

Allen said only a few civil lawsuits have been filed in child pornography cases, even though the option for victims to sue has been around for more than two decades.

New York attorney James Marsh pushed for a law Congress passed in 2006 that increased penalties for child pornography criminals and made it easier for victims to sue. Anderson filed the lawsuit under Masha's Law, named after one of Marsh's clients -- a girl adopted from Russia by a man in the U.S. who turned out to be a pedophile.

But Marsh himself has only used civil litigation on a limited basis, choosing instead to put pressure on federal prosecutors to seek restitution for victims in criminal cases.

Marsh said there are two main reasons lawsuits in child porn cases can be difficult. First, attorneys must file separate lawsuits if they want to go after all the people accused of distributing or viewing the image. Those suits need to be filed wherever the accused live, and when the Internet is involved, that could be anywhere.

Second, if the lawsuit is being filed on behalf of a minor, special court procedures are needed to establish a guardian for the child. Doing that in hundreds of cases in multiple states can be costly and time-consuming.

Marsh said just filing lawsuits against the 1,000 people who victimized one of his clients would have cost an estimated $450,000, not to mention other costs such as seeking permission to lawyer in another state or hiring other attorneys to help out. Marsh was able to settle the case instead.

"We don't have the structure in place in the federal courts to deal with this kind of issue and this kind of victimization," he said.

Anderson acknowledged he's entering uncharted territory, but he said the new pursuit is not unlike the action he started taking back in the 1980s on sexual abuse allegations against clergy in the Catholic Church. Going after perpetrators in other states or countries isn't new either -- Anderson sued the Vatican itself this year.

But questions remain as to what is the best way to compensate victims whose images have been viewed over and over.

Allen said Anderson's lawsuit has the potential to set a precedent for how such cases are handled in the future. But he said success isn't a guarantee.

"This is a probing effort to try to determine the best way to do this," he said. "Whether individual lawsuits on behalf of individual victims is the best way to proceed or not, I think time will tell."

Other options include developing clearer standards for victim restitution payments -- an effort federal prosecutors are already working on -- or setting up a designated victims' compensation fund. Such a fund could help any victim, Allen said.

"Civil litigation is expensive and many victims will not be able to take advantage of it," he said.

Even if Anderson's legal strategy doesn't deliver the $150,000 payment he's seeking from each person named in the suit -- the teacher and some 100 downloaders -- it's clear he has something else in mind: exposure.

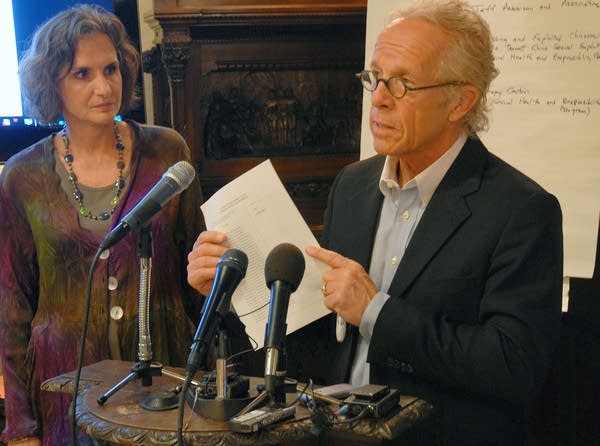

During the news conference in his office, Anderson repeated several times that he intended to track people down, expose them in the media and sue them. At times, he spoke directly to those who may have downloaded images of his client.

"We're here to let you know that you can be held accountable in a number of different ways," Anderson said. "We will make no secret of the fact that you have committed the crime. ... We will make no apology for making that known to the community in which you live, in which you work."