Rwandan judge says no bail for St. Paul professor

A Rwandan judge denied bail today for Minnesota law professor Peter Erlinder, who has been charged with denying Rwanda's 1994 genocide and publishing articles that threaten the country's security.

The judge said that Erlinder's lawyers have not shown a link between his sickness and being in detention. However, Sarah Erlinder, the law professor's daughter, said her father's attorneys were not allowed to introduce key medical documents at Monday's hearing.

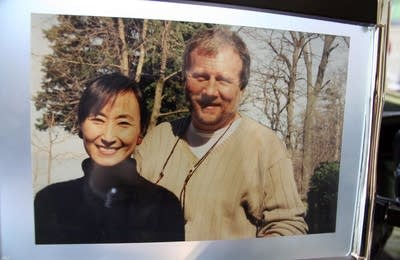

Erlinder, 62, has been hospitalized twice since he was arrested on May 28. His lawyers said they plan to appeal the bail decision in Rwanda's High Court.

The decision was a blow to Erlinder's family members, who were hoping he would be released and deported from the country today.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

"It's just very disappointing," Sarah Erlinder said. "I think we have to have that optimism, but it's very upsetting, and it continues to be this rollercoaster of bad news."

She said that Rwandan officials have transferred her father to Kigali Central Prison, a larger facility that she said holds over 3,000 inmates. She said she worries that her father's heart condition and high blood pressure will worsen under the stress of prison life. Erlinder's family has not spoken with him since his arrest, despite several requests to Rwandan officials.

The William Mitchell College of Law professor arrived in Rwanda several days before his arrest to represent a presidential candidate who has been charging with expressing illegal views on the country's genocide.

Erlinder has long argued that there was no premeditated effort to wipe out the ethnic Tutsi minority group before the genocide began in 1994.

"These were killings that went on between civilians in the country and were not part of any planned effort to exterminate a particular group," he said in a 2005 interview with MPR News.

Just two years ago, the constitutional law professor took his reasoning one step further. In an essay published on the legal news site Jurist, he wrote: "If there was no conspiracy and no planning to kill ethnic civilians, can the tragedy that engulfed Rwanda properly be called 'a genocide' at all?"

Erlinder's supporters say he never denied that mass violence broke out over three months in 1994 in Rwanda. An estimated 800,000 people were killed. They say Erlinder just wants both sides -- the Hutus and the Tutsis -- to share the blame.

And that is Erlinder's only crime, says Paul Rusesabagina. He's a former hotel manager whose story was told in the movie "Hotel Rwanda."

Rusesabagina says the current government's laws against so-called "genocide ideology" are so broad that even an American lawyer could get caught up in the tangle of prohibited speech in Rwanda.

"If you question the official Rwandan government version, then you became obviously a 'genocide denier,'" he said.

Human rights groups have also criticized Rwanda's genocide ideology law, which they say limits free speech.

But Rwanda's foreign minister, Louise Mushikiwabo, says she doesn't see much nuance in Erlinder's views. And she thinks they're dangerous because views like his could allow genocide to happen again.

"There is no question in my mind that Peter Erlinder denied the genocide. What he does is typical of genocide deniers. They always try to qualify it," she said. "I was very intrigued when I looked at his writings and his statements. He almost never mentions the word genocide. He always talks about 'massacres,' 'tragedy'..."

Although international pressure is mounting on the Rwandan government to free Erlinder, Mushikiwabo says that won't happen anytime soon. She disagrees with Erlinder's family and supporters who don't view his actions as true crimes.

"But what they fail to understand is this is Rwanda, and Rwanda is a country where genocide was committed, and for the past 16 years people have been guarding very preciously the social cohesion and the whole aspect of reconciling as a nation," she said. "It's extremely serious in this country."

Erlinder is the lead defense attorney for an international tribunal hearing the cases of the genocide's suspected masterminds. In a lawsuit he filed this year, Erlinder accused the current president, Paul Kagame, of ordering to shoot down a plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi back in 1994. The assassinations are credited with triggering the mass killings.

Erlinder has also accused the United States government of trying to cover up the killings carried out by President Kagame's forces. Erlinder said one of the co-conspirators was Brian Atwood, then the head of the U.S. Agency for International Development. Atwood is now the dean of the University of Minnesota's Humphrey Institute for Public Affairs. Atwood couldn't be reached for comment, but told the Associated Press that Rwanda's arrest of Erlinder was "a huge mistake."

Greg Stanton is a former State Department official who wrote the United Nations resolutions that created the international tribunal. Stanton says Erlinder's views are at odds with the main narrative accepted by most historians and others who have closely followed the Rwandan massacres.

"You know, that this was a genocide in Rwanda. It was one of the worst in history," Stanton said. "It was planned by the Hutu power movement, and most of the victims were Tutsi. I think you could find 99 percent agree on it."

Stanton says there is a growing revisionist movement, especially among Hutus now living in Europe and Canada, who deny the massacres happened at all. But he doesn't put Erlinder in that camp of genocide deniers. He says Erlinder is just doing his job as an attorney -- that is, to take an unpopular position while defending people who have done terrible things.

The Rwandan government, for its part, says it won't back down, and it's eager to make the case against Peter Erlinder at trial. Erlinder has five days to appeal the judge's ruling.

Meanwhile, Mushikiwabo said that the family's optimism that Erlinder would be released today wasn't realistic, given what she called the serious nature of the charges.

"It's highly unlikely that Rwanda would look at charges of genocide denial as something simple or symbolic, where the government could get pressure to release somebody," Mushikiwabo told MPR News on Monday.

Mushikiwabo says she looks forward to seeing the matter advance to a trial.

"This would be very interesting because Peter Erlinder gets to get his version of what he's doing. And our prosecution gets to prove that he's violating our laws," she said. "I would hope to see this play out in court soon."

(The Associated Press contributed to this report.)