Hearing today for Prairie Island concerns about nuclear waste storage

The Prairie Island Indian Community is asking the federal government to respond to its long-running concerns about nuclear waste stored near the Prairie Island power plant.

Members of the tribal group say more safety measures are needed, especially because the waste, stored in casks on a concrete pad, could be there for decades. The request follows a recent court ruling saying the current rules on waste storage are inadequate. Members of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission will take up the issue today in St. Paul.

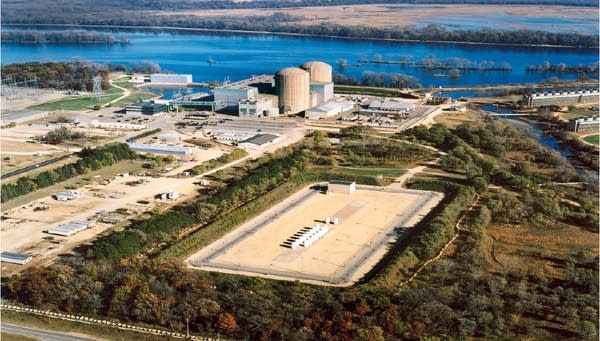

Some members of the Prairie Island Indian Community live just a couple of blocks from the twin reactors of Xcel Energy's nuclear power plant on the Mississippi River in Goodhue County. For years, they've been uneasy about the nuclear waste stored in 29 casks lined up behind an earthen berm next to the plant. The spent fuel bundles once provided the energy to produce electricity for 750,000 homes in the region; today the bundles are not useable but still radioactive.

Xcel Energy recently won permission to operate the plant for an additional 20 years. But the company needs the regulatory commission's permission to store the waste there longer. Eventually it will need 98 casks.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

Traditionally the NRC has said spent fuel can safely be stored on site for decades after a plant shuts down. Eventually the federal government plans to move the waste to a more permanent repository, but so far it has not done so.

Prairie Island Indian Community's General Counsel Phil Mahowald said the NRC is ignoring the government's failure to find a permanent location for the waste.

"Once that waste is on site you have to at least consider the possibility that it's going to be there indefinitely, for decades or perhaps even centuries," he said.

After the Prairie Island Indian Community and several states sued to compel the NRC to look more closely at the risks of on-site storage, a Washington D.C. appeals court ruled in June that the agency should have examined the possible environmental effects of temporary storage if the government never builds a repository.

Now that the agency has launched a two-year study of the stored waste, a key question is how long the waste might be in temporary locations like the one at Prairie Island. One possibility is 100 years.

Xcel Energy officials contend that that most of the tribe's concerns about the Prairie Island plant will be answered in the NRC's new overall review.

"The NRC has said they will take those issues up as they reexamine their rule," said Jim Alders, the company'' regulatory affairs strategy consultant. "That's really the best rulemaking process for addressing those, rather than our site-specific spent fuel storage license renewal."

The meeting in St. Paul is one stop in a long journey the Prairie Island Indian Community has taken to try to convince Xcel and the federal government to pay more attention to its concerns.

Mahowald said the tribe's fight speaks in part to environmental justice.

"If there were some type of incident or accident, the tribe would certainly feel the economic impacts of that probably more than any other group, just given its close proximity to the plant," he said.

The tribe is not the only group concerned about the safety of spent fuel storage.

David Lochbaum, director of the nuclear safety project at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a watchdog group, said the Nuclear Regulatory Commission is in a catch-22.

"If you judge that the fuel can't be stored safely and securely, where else will it go?" he asked. "You could move to another site where it would also not be stored safely and securely, but it's like a shell game, you can never make it go away. The end game needs to be looking at making it as safe and securely stored in the interim, whether that's ten years or 50 years."

In the Prairie Island case, Lochbaum said, the NRC will most likely approve Xcel Energy's application, perhaps adding some conditions requested by the tribe.

Lochbaum notes that dry cask storage is a lot safer than leaving spent fuel in pools, as scientists confirmed when a tsunami hit the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, Japan. The plant had more than 400 bundles of spent fuel in dry casks.

While crews used helicopters and fire trucks to dump water into the draining pools, Lochbaum said, tsunami waters covered the dry casks for a while. When the waters receded, the air worked to cool the fuel effectively, he said.

The NRC is expected to make a decision on Prairie Island within a couple of months.