FAQ: U drug trials, patient safety and the death of Dan Markingson

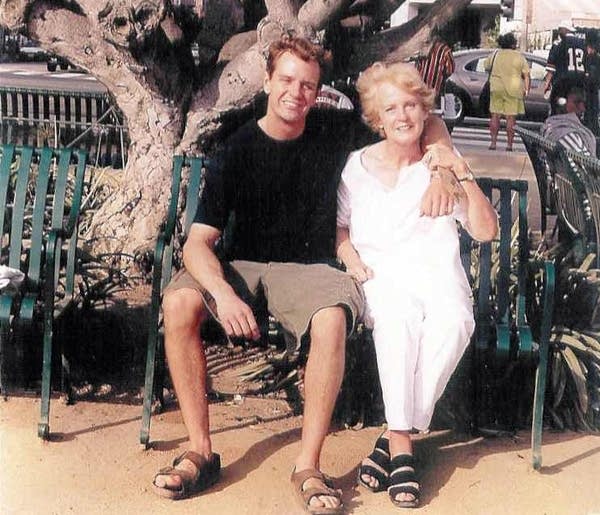

Dan Markingson and his mother, Mary Weiss. Weiss was concerned that her son wasn't getting better during his six months in a U of M study.

Courtesy Markingson family

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.