MSU team mapping Minnesota's Native American sites

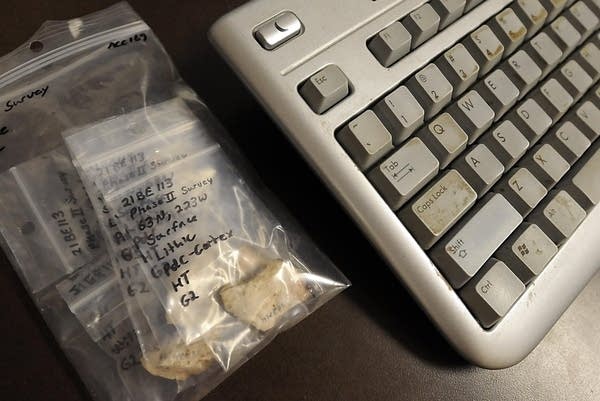

An artifact disconnected from place and time can be interesting as a piece of workmanship, but it usually tells archaeologists almost nothing.

"All meaning in archaeology starts with provenance," Minnesota State University professor Ron Schirmer said.

But all too often collections in Minnesota and elsewhere lack this crucial context about where an artifact was found and what was nearby. Differing labeling systems, a lack of documentation and spread-out collections confound academics and others who need to know about the state's artifacts.

Schirmer's own doctoral work in Red Wing had been stymied by artifacts cataloged in different places and systems, leaving him unable to make site-to-site comparisons. So, after years of running into this problem, he decided to do something.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

His vision is grand -- a database containing the locations of all of the state's roughly 18,000 Native American sites and millions of artifacts along with their accompanying notes, studies and field work.

While there have been smaller efforts to map archaeological sites, nothing on this scale has been attempted, Schirmer said. He knows of no other similar efforts nationwide, for that matter.

"It's an absolutely enormous task," he told The Free Press of Mankato.

The project recently received the go-ahead from the Minnesota Department of Transportation for a second year of funding, again at about $250,000. The money, which originates from the federal government, is matched at 20 percent by the university.

The transportation department might seem like an odd fit for an archaeological endeavor, but no agency performs as much of this research.

The project, called the Minnesota Archaeological Inventory Database, or MAID, is also expected to be used by researchers, the public and the Native American community.

American archaeologists have been excavating Native American sites for more than a hundred years, but these Natives' descendants have little or no access to that information, Schirmer said.

This year, Schirmer and his team of a dozen or so graduate students will contact area historical societies to investigate how they could include their collections in the database. A year from now, they hope to have a prototype with searchable data in it. For example, you could find, say, all of the triangular projection points in the state, organized by material type.

Schirmer's initial efforts were funded by the university's "Big Ideas" campaign. At first, he only wanted to organize the university's own holdings, estimated at more than 750,000 artifacts.

But then he had a much bigger idea: Organize all of the state's holdings, not just MSU's. He figured other institutions had the same problem, and a large project could serve them all.

There is indeed a vast array of archaeological information held across the state, said David Grabitske, who works in local history services at the Minnesota Historical Society. He also sits on the advisory committee for the MSU project.

"What he's trying to do, of course, is unify a lot of that material," he said of Schirmer. "To be able to say, well, this is where all of a certain kind of point might happen to be in the state."

Since the mid-'90s, the transportation department has been making efforts to map out archaeological sites, said Kristen Zschomler, who supervises MnDOT's cultural resources unit. They're also developing software to predict where artifact sites might be.

While this data has allowed the department to be more judicious about where to order archaeological surveys, it's not enough just to know where sites are.

"We need the rest of the story," Zschomler said. In other words, is the site just a few flakes where a hunter paused to sharpen an arrow or is it the remains of an entire village? The inventory would answer that question, at least for sites already investigated, with photos and details.

A comprehensive, searchable database has been on wish lists for some time.

"I think it was one of those things that a lot of archaeologists would say, 'Oh, wow, wouldn't that be great,' but never had any clue how to make it a reality," Zschomler said. "When he came to us and presented it, we were like, 'Yes, that would really be a benefit to our agency.'"

Her department works on hundreds of federally funded projects every year, and federal law requires them to be examined for their potential to impact a historic property.

Some of the work in creating the database is drudgery. On a recent Tuesday afternoon, archaeology graduate student Josh Anderson was scanning a thesis paper that evaluated several-hundred-year-old plant remains at two Blue Earth County sites. It happened to be Schirmer's own thesis, written at MSU in 1996.

The students plan to scan hundreds of thousands of pages of documents. That's a lot of work, but too many archaeological surveys just sit on shelves, nearly impossible to find, Schirmer said.

Nearby, anthropology graduate student Andy Brown was writing guides to get new students up to speed on programming. Much of the project involves figuring out how to unify data that had previously been fragmented or used for another purpose.

For example, the team had to use sophisticated software to stitch together hundreds of decades-old aerial photos of burial mounds. The same software was used to create three-dimensional images of artifacts using dozens of individual photographs.

As an example, Brown pulls up a 3-D model of a piece of pottery he found near Winnebago and flips it around to show the inside. The team used 187 images to make it, but that was an early effort and later models won't require nearly that many.

Photos are crucial, Schirmer said, because archaeologists use different terms to describe similar features.

Schirmer said the project is teaching the students skills they would never have a chance to learn elsewhere. And it's an example of how a teaching university such as MSU can incorporate research in a way that helps students, not just faculty.

No one, State Archaeologist Scott Anfinson said, believes this project will be finished in a few years.

"Even (Schirmer) knows the scope of the entire project is a lifetime undertaking," said Anfinson, who also sits on the project's advisory committee. It could take 10 or 20 years, he said, making a wild guess at what it would take to digitize and consolidate the state's archaeological knowledge in one place.

"You're going to need stick-to-it-iveness," he said. There will also be barriers. For example, Schirmer will be essentially telling every institution in the state that they'll need to use a standardized system.

"I don't see that going real smoothly," Anfinson said.

The state archaeologist's advice has been to split the project up into smaller chunks, such as MSU's holdings and those in nearby counties. But even at intermediate stages, the database will have value. Schirmer's team, for example, is doing valuable work scanning in old aerial photos of burial mounds, Anfinson said.

Dan Linehan, The Free Press of Mankato, AP Exchange