Nations at U.N. climate talks back universal emissions rules

After two weeks of bruising negotiations, officials from almost 200 countries agreed Saturday on universal, transparent rules that will govern efforts to cut emissions and curb global warming.

The deal agreed upon at U.N. climate talks in Poland enables countries to put into action the principles in the 2015 Paris climate accord.

But to the frustration of environmental activists and some countries who were urging more ambitious climate goals, negotiators delayed decisions on two key issues until next year in an effort to get a deal on them.

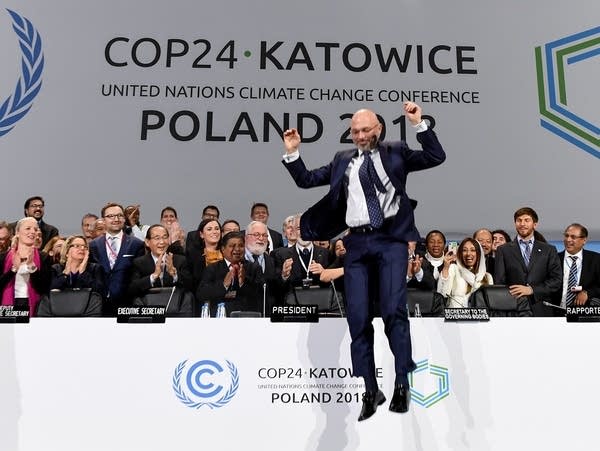

"Through this package, you have made a thousand little steps forward together," said Michal Kurtyka, a senior Polish official chairing the talks.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

He said while each individual country would likely find some parts of the agreement it didn't like, efforts had been made to balance the interests of all parties.

"We will all have to give in order to gain," he said. "We will all have to be courageous to look into the future and make yet another step for the sake of humanity."

The talks in Poland took place against a backdrop of growing concern among scientists that global warming on Earth is proceeding faster than governments are responding to it. Last month, a study found that global warming will worsen disasters such as the deadly California wildfires and the powerful hurricanes that have hit the United States this year.

And a recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, concluded that while it's possible to cap global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of the century compared to pre-industrial times, this would require a dramatic overhaul of the global economy, including a shift away from fossil fuels.

Alarmed by efforts to include this in the final text of the meeting, the oil-exporting nations of the U.S., Russia, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait blocked an endorsement of the IPCC report midway through this month's talks in the Polish city of Katowice. That prompted uproar from vulnerable countries like small island nations, and environmental groups.

The final text at the U.N. talks omits a previous reference to specific reductions in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, and merely welcomes the "timely completion" of the IPCC report, not its conclusions.

Last-minute snags forced negotiators in Katowice to go into extra time, after Friday's scheduled end of the conference had passed without a deal.

One major sticking point was how to create a functioning market in carbon credits. Economists believe that an international trading system could be an effective way to drive down greenhouse gas emissions and raise large amounts of money for measures to curb global warming.

But Brazil wanted to keep the piles of carbon credits it had amassed under an old system that developed countries say wasn't credible or transparent.

Among those that pushed back hardest was the United States, despite President Donald Trump's decision to pull out of the Paris climate accord and his promotion of coal as a source of energy.

"Overall, the U.S. role here has been somewhat schizophrenic — pushing coal and dissing science on the one hand, but also working hard in the room for strong transparency rules," said Elliot Diringer of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, a Washington think tank.

When it came to closing potential loopholes that could allow countries to dodge their commitments to cut emissions, "the U.S. pushed harder than nearly anyone else for transparency rules that put all countries under the same system, and it's largely succeeded."

"Transparency is vital to U.S. interests," added Nathaniel Keohane, a climate policy expert at the Environmental Defense Fund. He noted that breakthrough in the 2015 Paris talks happened only after the U.S. and China agreed on a common framework for transparency.

"In Katowice, the U.S. negotiators have played a central role in the talks, helping to broker an outcome that is true to the Paris vision of a common transparency framework for all countries that also provides flexibility for those that need it," said Keohane, calling the agreement "a vital step forward in realizing the promise of the Paris accord."

Among the key achievements in Katowice was an agreement on how countries should report their greenhouses gas emissions and the efforts they're taking to reduce them. Poor countries also secured assurances on getting greater predictability about financial support to help them cut emissions, adapt to inevitable changes such as sea level rises and pay for damages that have already happened.

"The majority of the rulebook for the Paris Agreement has been created, which is something to be thankful for," said Mohamed Adow, a climate policy expert at Christian Aid. "But the fact countries had to be dragged kicking and screaming to the finish line shows that some nations have not woken up to the urgent call of the IPCC report" on the dire consequences of global warming.

A central feature of the Paris Agreement — the idea that countries will ratchet up their efforts to fight global warming over time — still needs to be proved effective, he said.

"To bend the emissions curve, we now need all countries to deliver these revised plans at the special U.N. Secretary General summit in 2019. It's vital that they do so," Adow said.

In the end, a decision on the mechanics of an emissions trading system was postponed to next year's meeting. Countries also agreed to consider the issue of raising ambitions at a U.N. summit in New York next September.

Speaking hours before the final gavel, Canada's Environment Minister Catherine McKenna suggested there was no alternative to such meetings if countries want to tackle global problems, especially at a time when multilateral diplomacy is under pressure from nationalism.

"The world has changed, the political landscape has changed," she told the Associated Press. "Still you're seeing here that we're able to make progress, we're able to discuss the issues, we're able to come to solutions."