How did the Edmund Fitzgerald sink? A new book looks into the theories

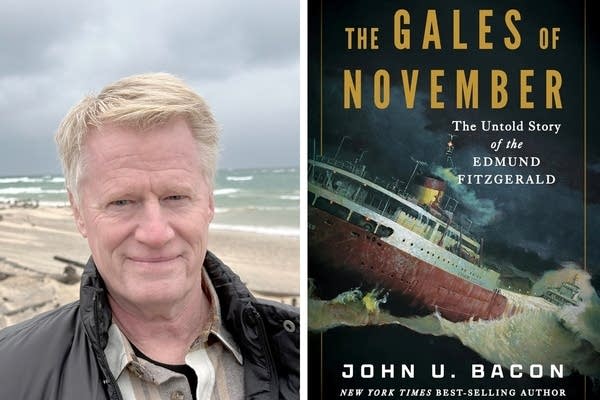

John U. Bacon is the author of the new book "The Gales of November: The Untold Story of the Edmund Fitzgerald."

Headshot photo by Roger Lelievre

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Audio transcript

DAN KRAKER: After all the work that you've done on this book, why do you think that this tragedy resonates so much still today, 50 years later?

JOHN U. BACON: It is kind of amazing that it still has a hold on the public. I'd say three things. One, without question, it's the song.

[GORDON LIGHTFOOT, "THE WRECK OF THE EDMUND FITZGERALD"] He said, fellas, it's been good to know ya

JOHN U. BACON: Between 1875 and 1975, there were more than 6,000 commercial shipwrecks on the Great Lakes. That's one per week every week for a century. And we all know one, and it's the Edmund Fitzgerald. And the reason is the song. You have to admit that.

[GORDON LIGHTFOOT, "THE WRECK OF THE EDMUND FITZGERALD"] In the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

JOHN U. BACON: Two, I think, is because there's still mystery surrounding it. It's very hard to say definitively why it sank. And finally, here's a crazy stat, Dan, is that since November 10, 1975, after 6,000 shipwrecks in a century, there's been not one since. So the Edmund Fitzgerald was so shocking it woke up the whole industry. So it's the last one that we've had, knock on wood. So you think about it quite readily, I think. So those three reasons, I think, are why.

DAN KRAKER: So you talked about the mystery. And we'll never exactly what happened, but that there are a lot of theories as to what may have caused the ship's demise. Could you get into a little bit about what some of those competing theories have been over the years?

JOHN U. BACON: Sure. There are several theories. The Coast Guard had a report shortly after the accident saying that they believe the hatches-- there are 21 gigantic hatches on these ships, and that's where you load the taconite. Taconite are little rusty pebbles of iron ore, basically. There are 81 latches per hatch, and that's about 1,400 per ship. It's a crazy number. And the deckhands' job is to latch these Kestner clamps, kind of like a C-clamp. And the Coast Guard's theory was they were not properly done or not done at all. And therefore, these hatches blew up, and therefore, the water got in.

And that theory, I hate to say, does not hold much water. So based on the interviews I've had with the previous deckhands that summer, even, who said there's no way you go out in November without all of them hatched, and what we've seen so far in the bottom seems to confirm what they say. So that seems pretty unlikely on the grand scale.

Other theories are that it cracked on the surface, which is certainly possible. Other ships have. And you wonder, how can that happen? Well, Great Lakes waves are so crazy that-- unlike the saltwater waves. On the ocean, saltwater smashes down the tops of the waves, basically, and spreads them out. But not in the Great Lakes. Great Lakes, they're sharp and pointy, like a mountain range, and they're twice as close together.

So on the ocean, they're 10 to 16 seconds apart. On the Great Lakes, they're 4 to 8 seconds apart. Why does that matter? You can have your bow in one 30 foot wave. You can have your stern in another 30 foot wave with nothing supporting it in the middle except for 26,000 tons of taconite. That's the same weight as 4,200 adult elephants. So with nothing supporting it, it can crack, and that has happened in the past.

And another possibility adding to all this is that it might have bottomed out on Six Fathom Shoal. That's an area by a tiny island called Caribou Island in the northeast corner of Lake Superior, and the Anderson that was sailing behind it, the captain there, Bernie Cooper, is convinced and has testified that he saw the Fitzgerald go over that shoals on his radar, and that might have damaged the bottom, which would bring water aboard from the bottom. So that's another theory as well. And it could be, of course, a combination of all the above.

Honestly, Dan, when you boil it all down, I go back to Ruth Hudson. She's the mother of Bruce Hudson, one of the 22-year-old deckhands on the ship. That was her only child, also. It's heartbreaking. She said, ultimately, only 30 know, 29 men and God, and nobody's talking.

DAN KRAKER: One of the aspects of this story that I find so fascinating is that the Arthur Anderson was close behind in communicating with the Fitzgerald for so long. And I know that ship sustained damage, but it emerged relatively unscathed, right?

JOHN U. BACON: That's correct. I managed to find a guy, Rick Barthuli, who had been a second engineer on that ship, on the Arthur Andersen that night. And that's as close as we can get to an eyewitness. And he said, we're an hour behind. Why are we on hour behind/ Because Fitzgerald, when it took most of that trip, was still going full speed, was racing. And that takes a greater toll on your ship, naturally. That's one aspect.

Another aspect is they swapped out, when they built the Fitzgerald, thousands of rivets for welds. And why did you do that? Welds are 1.2 million pounds lighter overall than the rivets. So now, you can carry 1.2 million more pounds of iron on every trip. This ship makes 50 trips a year from Minnesota, basically, to Toledo and back. That adds up very quickly, but it makes it more flexible. This was more flexible than its peers and probably shouldn't have been.

DAN KRAKER: It sounds like part of the tragedy was driven by this competition on the lakes to be, what? To be the fastest? To carry the most ore?

JOHN U. BACON: Yeah, exactly right. The captains got along, by and large, pretty well. But you're always in competition. Why? If I beat your ship by 10 feet, I just gained an hour over you. And if I gain an hour over you, I get to the docks first, and that can cost you 10 or 14 hours. So ten seconds, it turns out, can be half a day. Bernie Cooper, the captain of the Anderson chasing the Edmund Fitzgerald, said no company ever paid a captain to lay on the hook, as they say, to put the anchor down. You're paid to go. And these guys did, and they're very competitive.

DAN KRAKER: John, can we go back to that fateful night? I know you've written about McSorley as being quite an accomplished captain, but take us back to that night and some of the choices he made that led up to what happened.

JOHN U. BACON: Well, Dan, this story is heartbreaking on a lot of levels. And the more I learned about it, frankly, the more heartbreaking it got. Captain Ernest McSorley was, by all accounts-- even his rivals said this. He was the greatest captain on the Great Lakes. He was the youngest captain at age 31 when he first became a captain in 1943. And now, he's 63. He's been a captain in the Great Lakes more than half his life.

But he made some decisions decision that night that, in hindsight, we can say did not work out as planned. Shortly after they leave Superior, Wisconsin, at 2:00 on Sunday afternoon, November 9, they're joined a few hours later by the Arthur Anderson leaving Two Harbors, Minnesota. They're going together, and early on, they realize they're in for a storm. So they decide to take what's called the northern route.

Usually, you just goes as far south as you can along Lake Superior-- the straightest line, naturally. But the northern route means you're going to be basically hugging the shore of Lake Superior, the Canadian sides. But it comes with three problems. One, it's pay me now or pay me later. So the first two legs are going to be better, but your last leg going down the eastern coast of Lake Superior is going to be far worse.

Now, these waves have had 350 miles to gain speed, momentum, height, and power. And they're going to hit you with your ship broadside, which means on the side of it. That's the last way you want to wave to hit you, because now, you're rolling back and forth in danger of capsizing. So captains don't like that.

Second thing is, it's 14 hours longer, so he just gave that southern storm a 14 hour head start. Third problem is you don't it as well. So when you're coming down the last leg, his long radar was out. His short radar is out. The light at the Whitefish Point Lighthouse, that went out that night. Just dumb luck. And the radio beacon also went out due to the weather. He's sailing blind.

DAN KRAKER: And take us back to that moment, John, that fateful last radio message that he made where he said, what? That he's holding his own, right?

JOHN U. BACON: That's right. So he calls Bernie Cooper. He's got a fence railing down. He's complaining to Cooper about all these things. And he mentions, kind of in passing, he's got a starboard list. That means the ship is tilting constantly to the right side. And that's a problem for a few reasons. It's harder to steer that way. You're far more vulnerable to a big wave taking you down or cracking you at that point.

And then a few hours later, when he's talking to Bernie Cooper again in these crazy 30 foot waves, that's the first thing that he mentions is the starboard list, which tells us it's probably getting worse. So now, he knows he's got a problem. At 7:00, he's got real problems. He's just trying to get to Whitefish Bay. And Cooper asks him, how are you making out with your problems? And Ernest McSorley says, and I quote, "We are holding our own." And those are the last words anybody knows from the Edmund Fitzgerald.

DAN KRAKER: And he wasn't that far from safety, right?

JOHN U. BACON: Man. Only 17 miles from safety. That's only an hour in one of these ships.

DAN KRAKER: So John, I know you had the opportunity to talk to a lot of family members of some of the sailors who perished in this tragedy. From talking to all those folks, were there common themes you heard from them or messages they wanted to get across to the public about this?

JOHN U. BACON: I found a few common themes, as you say. One, these are all blue collar families who depended on these men, often their fathers, for their income. So there's a huge loss, naturally. Two, it's a hard life before anything horrible really happens. Their dads were on these ships for nine months a year. No weddings, no graduations, no birthdays. As one of the sailors told me, I've got three kids. I never taught any of them how to ride a bike. So these families already sacrificed long before the accident.

I also learned just how important Great Lakes shipping is, not just to the region, but to the world. This is the cement in your basement. This is the steel in your car. This is the food in your table. It all comes from Great Lakes sailors. I was also surprised to learn from the families that they really don't care that much to solve the mystery of why the ship went down. As I talked to them, they said, my dad's been gone for 49 years. What difference could it possibly make?

And finally, I'd say one more thing, that insurance didn't pay much because they could claim it's an act of God. The shipping company itself, they paid the least possible, usually a year's salary to their families. That's not very much when you have seven kids at home. So I was talking to Heidi Wilhelm Brabon now. She was a 12-year-old girl when this happened. And they didn't find out from the company. The company called nobody and returned no calls. Just plain cruel, in my view.

They found out because of Dennis Anderson on Channel 10 in Duluth. And he reported that night, and that's when the neighbors of the Wilhelms knocked on the door at 10:00 at night saying, your dad's ship is gone. I mean, imagine that. So what do they do? They sucked it up. And they got to state schools. They joined the military. They raised kids. There was a beautiful silver lining here.

The crew members on this ship were unusually close. It was a very unified ship. Very unusually so, frankly. I've gotten that from guys who were on the ship with them. But the families did not each other at all. About one third Duluth area, one third Toledo, one third Cleveland. And yet after this happened, this brought them very close.

And Heidi said to me, around this table at Whitefish Point, at the 48th reunion, she grabs the forearms of two of her fellow victims, if you will, and said, these people are not like family, they are family. Her daughter, Sarah, who was born on the 23rd anniversary of the sinking of her grandfather's ship, a grandfather she never met, obviously. And then on her 21st birthday, she got a tattoo. And it says, "We are holding our own." And these families really have. It gets me every time.

[GORDON LIGHTFOOT, "THE WRECK OF THE EDMUND FITZGERALD"] The church bell chimed till it rang 29 times for each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald

JOHN U. BACON: My whole goal, Dan, in writing the book was not just to figure out what happened. Certainly, it's on my mind, and we tried to advance certain theories and diminish others, but we can't solve that. My whole goal was to make the 29 men turn from a number to actual human beings.

[GORDON LIGHTFOOT, "THE WRECK OF THE EDMUND FITZGERALD"] When the gales of November come early

JOHN U. BACON: It is kind of amazing that it still has a hold on the public. I'd say three things. One, without question, it's the song.

[GORDON LIGHTFOOT, "THE WRECK OF THE EDMUND FITZGERALD"] He said, fellas, it's been good to know ya

JOHN U. BACON: Between 1875 and 1975, there were more than 6,000 commercial shipwrecks on the Great Lakes. That's one per week every week for a century. And we all know one, and it's the Edmund Fitzgerald. And the reason is the song. You have to admit that.

[GORDON LIGHTFOOT, "THE WRECK OF THE EDMUND FITZGERALD"] In the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

JOHN U. BACON: Two, I think, is because there's still mystery surrounding it. It's very hard to say definitively why it sank. And finally, here's a crazy stat, Dan, is that since November 10, 1975, after 6,000 shipwrecks in a century, there's been not one since. So the Edmund Fitzgerald was so shocking it woke up the whole industry. So it's the last one that we've had, knock on wood. So you think about it quite readily, I think. So those three reasons, I think, are why.

DAN KRAKER: So you talked about the mystery. And we'll never exactly what happened, but that there are a lot of theories as to what may have caused the ship's demise. Could you get into a little bit about what some of those competing theories have been over the years?

JOHN U. BACON: Sure. There are several theories. The Coast Guard had a report shortly after the accident saying that they believe the hatches-- there are 21 gigantic hatches on these ships, and that's where you load the taconite. Taconite are little rusty pebbles of iron ore, basically. There are 81 latches per hatch, and that's about 1,400 per ship. It's a crazy number. And the deckhands' job is to latch these Kestner clamps, kind of like a C-clamp. And the Coast Guard's theory was they were not properly done or not done at all. And therefore, these hatches blew up, and therefore, the water got in.

And that theory, I hate to say, does not hold much water. So based on the interviews I've had with the previous deckhands that summer, even, who said there's no way you go out in November without all of them hatched, and what we've seen so far in the bottom seems to confirm what they say. So that seems pretty unlikely on the grand scale.

Other theories are that it cracked on the surface, which is certainly possible. Other ships have. And you wonder, how can that happen? Well, Great Lakes waves are so crazy that-- unlike the saltwater waves. On the ocean, saltwater smashes down the tops of the waves, basically, and spreads them out. But not in the Great Lakes. Great Lakes, they're sharp and pointy, like a mountain range, and they're twice as close together.

So on the ocean, they're 10 to 16 seconds apart. On the Great Lakes, they're 4 to 8 seconds apart. Why does that matter? You can have your bow in one 30 foot wave. You can have your stern in another 30 foot wave with nothing supporting it in the middle except for 26,000 tons of taconite. That's the same weight as 4,200 adult elephants. So with nothing supporting it, it can crack, and that has happened in the past.

And another possibility adding to all this is that it might have bottomed out on Six Fathom Shoal. That's an area by a tiny island called Caribou Island in the northeast corner of Lake Superior, and the Anderson that was sailing behind it, the captain there, Bernie Cooper, is convinced and has testified that he saw the Fitzgerald go over that shoals on his radar, and that might have damaged the bottom, which would bring water aboard from the bottom. So that's another theory as well. And it could be, of course, a combination of all the above.

Honestly, Dan, when you boil it all down, I go back to Ruth Hudson. She's the mother of Bruce Hudson, one of the 22-year-old deckhands on the ship. That was her only child, also. It's heartbreaking. She said, ultimately, only 30 know, 29 men and God, and nobody's talking.

DAN KRAKER: One of the aspects of this story that I find so fascinating is that the Arthur Anderson was close behind in communicating with the Fitzgerald for so long. And I know that ship sustained damage, but it emerged relatively unscathed, right?

JOHN U. BACON: That's correct. I managed to find a guy, Rick Barthuli, who had been a second engineer on that ship, on the Arthur Andersen that night. And that's as close as we can get to an eyewitness. And he said, we're an hour behind. Why are we on hour behind/ Because Fitzgerald, when it took most of that trip, was still going full speed, was racing. And that takes a greater toll on your ship, naturally. That's one aspect.

Another aspect is they swapped out, when they built the Fitzgerald, thousands of rivets for welds. And why did you do that? Welds are 1.2 million pounds lighter overall than the rivets. So now, you can carry 1.2 million more pounds of iron on every trip. This ship makes 50 trips a year from Minnesota, basically, to Toledo and back. That adds up very quickly, but it makes it more flexible. This was more flexible than its peers and probably shouldn't have been.

DAN KRAKER: It sounds like part of the tragedy was driven by this competition on the lakes to be, what? To be the fastest? To carry the most ore?

JOHN U. BACON: Yeah, exactly right. The captains got along, by and large, pretty well. But you're always in competition. Why? If I beat your ship by 10 feet, I just gained an hour over you. And if I gain an hour over you, I get to the docks first, and that can cost you 10 or 14 hours. So ten seconds, it turns out, can be half a day. Bernie Cooper, the captain of the Anderson chasing the Edmund Fitzgerald, said no company ever paid a captain to lay on the hook, as they say, to put the anchor down. You're paid to go. And these guys did, and they're very competitive.

DAN KRAKER: John, can we go back to that fateful night? I know you've written about McSorley as being quite an accomplished captain, but take us back to that night and some of the choices he made that led up to what happened.

JOHN U. BACON: Well, Dan, this story is heartbreaking on a lot of levels. And the more I learned about it, frankly, the more heartbreaking it got. Captain Ernest McSorley was, by all accounts-- even his rivals said this. He was the greatest captain on the Great Lakes. He was the youngest captain at age 31 when he first became a captain in 1943. And now, he's 63. He's been a captain in the Great Lakes more than half his life.

But he made some decisions decision that night that, in hindsight, we can say did not work out as planned. Shortly after they leave Superior, Wisconsin, at 2:00 on Sunday afternoon, November 9, they're joined a few hours later by the Arthur Anderson leaving Two Harbors, Minnesota. They're going together, and early on, they realize they're in for a storm. So they decide to take what's called the northern route.

Usually, you just goes as far south as you can along Lake Superior-- the straightest line, naturally. But the northern route means you're going to be basically hugging the shore of Lake Superior, the Canadian sides. But it comes with three problems. One, it's pay me now or pay me later. So the first two legs are going to be better, but your last leg going down the eastern coast of Lake Superior is going to be far worse.

Now, these waves have had 350 miles to gain speed, momentum, height, and power. And they're going to hit you with your ship broadside, which means on the side of it. That's the last way you want to wave to hit you, because now, you're rolling back and forth in danger of capsizing. So captains don't like that.

Second thing is, it's 14 hours longer, so he just gave that southern storm a 14 hour head start. Third problem is you don't it as well. So when you're coming down the last leg, his long radar was out. His short radar is out. The light at the Whitefish Point Lighthouse, that went out that night. Just dumb luck. And the radio beacon also went out due to the weather. He's sailing blind.

DAN KRAKER: And take us back to that moment, John, that fateful last radio message that he made where he said, what? That he's holding his own, right?

JOHN U. BACON: That's right. So he calls Bernie Cooper. He's got a fence railing down. He's complaining to Cooper about all these things. And he mentions, kind of in passing, he's got a starboard list. That means the ship is tilting constantly to the right side. And that's a problem for a few reasons. It's harder to steer that way. You're far more vulnerable to a big wave taking you down or cracking you at that point.

And then a few hours later, when he's talking to Bernie Cooper again in these crazy 30 foot waves, that's the first thing that he mentions is the starboard list, which tells us it's probably getting worse. So now, he knows he's got a problem. At 7:00, he's got real problems. He's just trying to get to Whitefish Bay. And Cooper asks him, how are you making out with your problems? And Ernest McSorley says, and I quote, "We are holding our own." And those are the last words anybody knows from the Edmund Fitzgerald.

DAN KRAKER: And he wasn't that far from safety, right?

JOHN U. BACON: Man. Only 17 miles from safety. That's only an hour in one of these ships.

DAN KRAKER: So John, I know you had the opportunity to talk to a lot of family members of some of the sailors who perished in this tragedy. From talking to all those folks, were there common themes you heard from them or messages they wanted to get across to the public about this?

JOHN U. BACON: I found a few common themes, as you say. One, these are all blue collar families who depended on these men, often their fathers, for their income. So there's a huge loss, naturally. Two, it's a hard life before anything horrible really happens. Their dads were on these ships for nine months a year. No weddings, no graduations, no birthdays. As one of the sailors told me, I've got three kids. I never taught any of them how to ride a bike. So these families already sacrificed long before the accident.

I also learned just how important Great Lakes shipping is, not just to the region, but to the world. This is the cement in your basement. This is the steel in your car. This is the food in your table. It all comes from Great Lakes sailors. I was also surprised to learn from the families that they really don't care that much to solve the mystery of why the ship went down. As I talked to them, they said, my dad's been gone for 49 years. What difference could it possibly make?

And finally, I'd say one more thing, that insurance didn't pay much because they could claim it's an act of God. The shipping company itself, they paid the least possible, usually a year's salary to their families. That's not very much when you have seven kids at home. So I was talking to Heidi Wilhelm Brabon now. She was a 12-year-old girl when this happened. And they didn't find out from the company. The company called nobody and returned no calls. Just plain cruel, in my view.

They found out because of Dennis Anderson on Channel 10 in Duluth. And he reported that night, and that's when the neighbors of the Wilhelms knocked on the door at 10:00 at night saying, your dad's ship is gone. I mean, imagine that. So what do they do? They sucked it up. And they got to state schools. They joined the military. They raised kids. There was a beautiful silver lining here.

The crew members on this ship were unusually close. It was a very unified ship. Very unusually so, frankly. I've gotten that from guys who were on the ship with them. But the families did not each other at all. About one third Duluth area, one third Toledo, one third Cleveland. And yet after this happened, this brought them very close.

And Heidi said to me, around this table at Whitefish Point, at the 48th reunion, she grabs the forearms of two of her fellow victims, if you will, and said, these people are not like family, they are family. Her daughter, Sarah, who was born on the 23rd anniversary of the sinking of her grandfather's ship, a grandfather she never met, obviously. And then on her 21st birthday, she got a tattoo. And it says, "We are holding our own." And these families really have. It gets me every time.

[GORDON LIGHTFOOT, "THE WRECK OF THE EDMUND FITZGERALD"] The church bell chimed till it rang 29 times for each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald

JOHN U. BACON: My whole goal, Dan, in writing the book was not just to figure out what happened. Certainly, it's on my mind, and we tried to advance certain theories and diminish others, but we can't solve that. My whole goal was to make the 29 men turn from a number to actual human beings.

[GORDON LIGHTFOOT, "THE WRECK OF THE EDMUND FITZGERALD"] When the gales of November come early

Download transcript (PDF)

Transcription services provided by 3Play Media.