At St. John's, a quest to save ancient texts

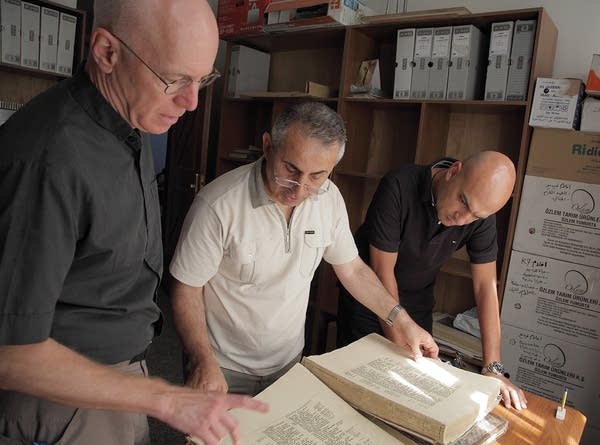

The Rev. Columba Stewart, the Rev. Nageeb Michaeel and Walid Mourad examined a printed Bible at the Dominican Priory in Qaraqosh, Iraq, home of the Centre Numerique des Manuscrits Orientaux.

Courtesy Hill Museum & Manuscript Library

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.