9 facts about emotional memories and recall

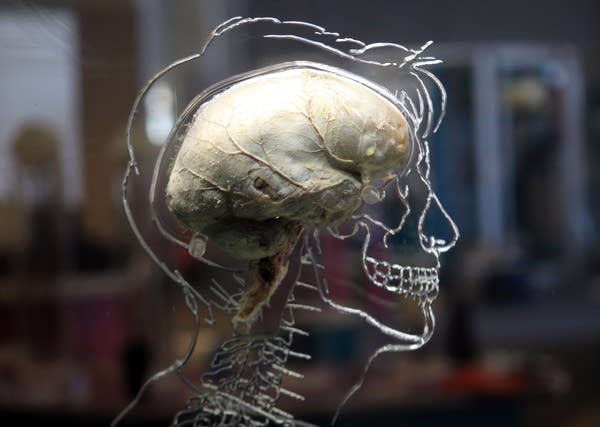

A real human brain displayed as part of new exhibition at the Bristol attraction March 8, 2011 in Bristol, England.

Matt Cardy | Getty Images

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.