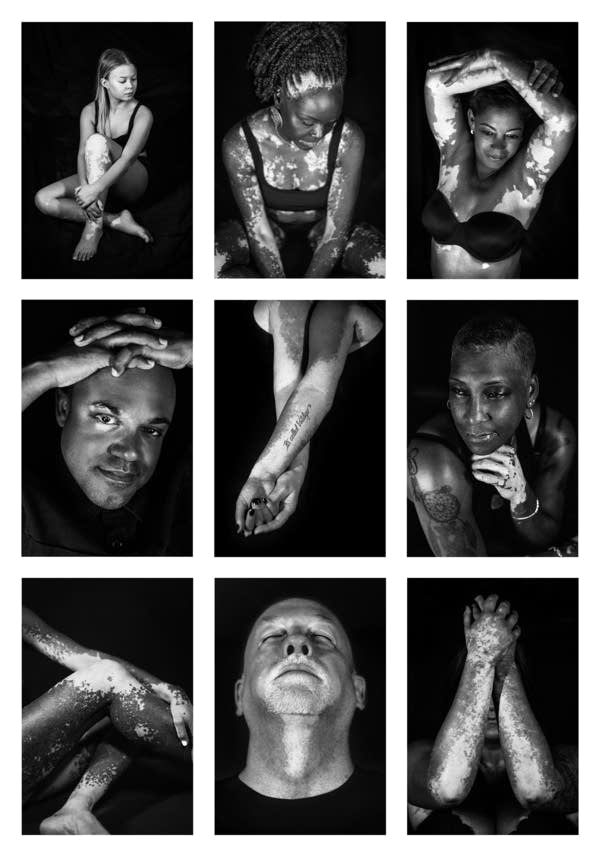

Using black lights, a photographer captures her and other's journey with vitiligo

Portraits by Minnesota-based photographer Sharolyn B. Hagen show individuals living with vitiligo, a non-contagious autoimmune condition that causes depigmented patches of skin. Since 2022, Hagen has expanded her personal project to include others from across Minnesota, aiming to increase representation and understanding of vitiligo.

Photos courtesy of Sharolyn B. Hagen

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Audio transcript

NINA MOINI: A local artist is working to humanize people living with vitiligo through photographs that use black lights to highlight the skin condition. Vitiligo is the autoimmune disorder that causes white patches to appear on the skin. And it affects almost 1% of people worldwide.

Sharolyn Hagen started taking photographs of herself when she was diagnosed with vitiligo in 2016, to track the progression of her condition. But it turned into a much larger art and advocacy project, and she's here in the studio to explain. Thank you so much for being here, Sharolyn.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Thank you for having me.

NINA MOINI: Thank you for sharing your beautiful work with us. And people can check it out, obviously, online. But what do you tell people who may not be very familiar or know somebody who lives with vitiligo about it?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: So originally, it was considered just more of like a cosmetic problem since it's not life-threatening or painful. But over the years, with more funding, they've found that actually, it's a psychosocial disorder, where it can really affect people in how they-- if they even leave their houses, or if they are OK with being in public without being covered.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. I mean, people have so many different experiences and different backgrounds that contribute to just how they're living their lives, probably, with vitiligo. When you talk about it as having been more of a cosmetic thing before and now people realizing, no, this impacts like the spectrum of your life, tell me a little bit about how you approach others when you want to photograph them, depending on how they feel about that. How does that conversation go?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Yeah. So I'm part of a group called Minnesota Vit Friends, and they had seen my original self-portrait series, and we had talked about wanting to do it for more people in our group. And some of them were obviously very hesitant, because most times, if you ask people about being in a black light, they'll be like, with vitiligo? No way. It's not very flattering.

But that's exactly the look that I'm going for to add the contrast to it. So I just have to approach it with having as much empathy and compassion since I have it, and knowing that it is a very vulnerable situation. But the goal is to help them feel beautiful and empowered.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. And so it was 2016. You were already a working photographer and had that passion. Was it a difficult choice to turn the camera on yourself?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: No, it was just a natural, like, no-brainer. It just made sense that I wanted to do that. Yeah. But at first, it was kind of more medical documentation.

NINA MOINI: Sure.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: And then it turned into a little bit, more of an artistic.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. Tell me a little bit more about the lighting, if you would. You mentioned people are initially, like, oh, I don't about the black light, but--

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Yeah.

NINA MOINI: --how did you choose the way you did it?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: So when I was diagnosed, at the University of Minnesota, they turn off the lights in the exam room and bring out a Wood's lamp, which is a high powered UV light. And because of that, I was shown spots that I didn't even know I had. And so I asked them if it would be safe for me to use as a photo series. And they acknowledged that as long as it was short periods of time and things like that, that it would definitely change the contrast in the images.

NINA MOINI: What do you think the hope is with this work? What do you want people with vitiligo, and people without, and just everybody to hopefully take away or see?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: I'm surprised when I run into people out in the world that live around here that don't know there's a group of people that get together and support each other and educate each other.

And I just hope that if there's somebody out there that has a kid that feels lonely or doesn't understand-- because kids can be so harsh, you know? And so, if they're hearing about this and seeing, like, oh, wait, I see somebody who has this me, maybe I don't have to hide. Maybe I can, you know, feel a little bit more comfortable in my own skin.

NINA MOINI: And do you know if people typically have this experience? I mean, you were older, right? I mean, is this like mostly in childhood, or does it vary? Do you know?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: It can vary. It's more likely if you get diagnosed with it when you're a kid, it's genetic, if it's somebody else in your family has it. But it can develop at any age. I was in my mid-30s, and came out of nowhere, so.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. And you mentioned how this is a part of people's entire life. Do you ever talk to people who feel that they've been judged or have lost out on opportunities? I mean, what are some of the real-life experiences you or others have struggled with?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Well, I feel pretty fortunate to live in this day and age and in the country that I do, because still, even now in some countries, if you have it, you are not allowed to get married. You're not allowed to reproduce. You're kind of shunned from public. Even your family members, if they don't have it.

So just the fact that here, there's more acceptance being gained as more funding is being put towards research and the word out there. Yeah.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. Remind us how people can see your work or access it. Like, do you take it to different places and display it to get the word out, or how is it going to work?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Yeah. So I already have a line up of more people who are ready for the next session. And another event with the big, large portraits will be in the works. My Instagram is my full name, Sharolyn_Hagen_Photo, and also, my website, sbhphotography.com.

NINA MOINI: You mentioned the support group that you're a part of, and that's just great that, that exists. It's more grassroots or kind of organically driven, it seems. Tell us, if you would, just what are the resources beyond that? Are there a lot of resources beyond that, or is it kind of people within the community helping one another out?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Even within the past 10 years, it's changed quite a bit. There's The Global Vitiligo Foundation that does an annual conference, and it can be hundreds of people who come together for one weekend. And it's around World Vitiligo Day, which is June 25.

NINA MOINI: And did you go to that/

SHAROLYN HAGEN: I have been to the one. They had it in Minneapolis in 2022.

NINA MOINI: Cool.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: And I hope to get to the next one, as well. And that, just being surrounded with a room full of people that all have it, is just, I can't even explain how safe and great it feels to know that people understand.

NINA MOINI: And you mentioned that sometimes people could be reluctant in the beginning to allow you to photograph them. But I do wonder, too, what it's like for them to see the images? And if there's a special way that you like to reveal that, or if some-- and then, what is the reaction, and how does that make you feel?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Yeah. So originally when I take them, we do like a handful of the best shots for people to help narrow down which ones we want to print for the series. And I'll never forget, one of the women showed up at a event that we had where it was-- it's a big 24 by 36 inch print. And she stood there, and she just put her hand over her mouth, and she got teary. And she was like, "I never like photos of myself, and this makes me feel beautiful." And that just, like-- that's the whole reason. Yeah.

NINA MOINI: Wow. That is beautiful. And have you thought about ways to bring your work to greater audiences? What do you think about? What would be next for showcasing this work on more platforms?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Yeah. So, a dream job would be to just to travel the world and photograph people with vitiligo.

NINA MOINI: Oh, that would be cool.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: I was flown to Orlando, Florida, this spring to go to a dermatologist symposium, where there was about 125 people all from around the world that are studying vitiligo. And I was able to speak as a patient advocate and talk to-- of course, there are some people in big pharma that were there that mentioned that there's opportunities for grants and things like that. So I'm looking into--

NINA MOINI: Well--

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Maybe.

NINA MOINI: --just thinking about expanding and bringing your work to more people.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Exactly.

NINA MOINI: Beautiful work. Thank you so very much for coming by Minnesota Now. Thank you for coming in the studio and sharing it with us. I really appreciate it.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Thanks for helping spread awareness.

NINA MOINI: Thank you, Sharolyn. That was photographer Sharolyn Hagen. You can see again the photographs of Sharolyn and the others with vitiligo. Head to our website, mprnews.org. We'll have her information there.

Sharolyn Hagen started taking photographs of herself when she was diagnosed with vitiligo in 2016, to track the progression of her condition. But it turned into a much larger art and advocacy project, and she's here in the studio to explain. Thank you so much for being here, Sharolyn.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Thank you for having me.

NINA MOINI: Thank you for sharing your beautiful work with us. And people can check it out, obviously, online. But what do you tell people who may not be very familiar or know somebody who lives with vitiligo about it?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: So originally, it was considered just more of like a cosmetic problem since it's not life-threatening or painful. But over the years, with more funding, they've found that actually, it's a psychosocial disorder, where it can really affect people in how they-- if they even leave their houses, or if they are OK with being in public without being covered.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. I mean, people have so many different experiences and different backgrounds that contribute to just how they're living their lives, probably, with vitiligo. When you talk about it as having been more of a cosmetic thing before and now people realizing, no, this impacts like the spectrum of your life, tell me a little bit about how you approach others when you want to photograph them, depending on how they feel about that. How does that conversation go?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Yeah. So I'm part of a group called Minnesota Vit Friends, and they had seen my original self-portrait series, and we had talked about wanting to do it for more people in our group. And some of them were obviously very hesitant, because most times, if you ask people about being in a black light, they'll be like, with vitiligo? No way. It's not very flattering.

But that's exactly the look that I'm going for to add the contrast to it. So I just have to approach it with having as much empathy and compassion since I have it, and knowing that it is a very vulnerable situation. But the goal is to help them feel beautiful and empowered.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. And so it was 2016. You were already a working photographer and had that passion. Was it a difficult choice to turn the camera on yourself?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: No, it was just a natural, like, no-brainer. It just made sense that I wanted to do that. Yeah. But at first, it was kind of more medical documentation.

NINA MOINI: Sure.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: And then it turned into a little bit, more of an artistic.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. Tell me a little bit more about the lighting, if you would. You mentioned people are initially, like, oh, I don't about the black light, but--

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Yeah.

NINA MOINI: --how did you choose the way you did it?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: So when I was diagnosed, at the University of Minnesota, they turn off the lights in the exam room and bring out a Wood's lamp, which is a high powered UV light. And because of that, I was shown spots that I didn't even know I had. And so I asked them if it would be safe for me to use as a photo series. And they acknowledged that as long as it was short periods of time and things like that, that it would definitely change the contrast in the images.

NINA MOINI: What do you think the hope is with this work? What do you want people with vitiligo, and people without, and just everybody to hopefully take away or see?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: I'm surprised when I run into people out in the world that live around here that don't know there's a group of people that get together and support each other and educate each other.

And I just hope that if there's somebody out there that has a kid that feels lonely or doesn't understand-- because kids can be so harsh, you know? And so, if they're hearing about this and seeing, like, oh, wait, I see somebody who has this me, maybe I don't have to hide. Maybe I can, you know, feel a little bit more comfortable in my own skin.

NINA MOINI: And do you know if people typically have this experience? I mean, you were older, right? I mean, is this like mostly in childhood, or does it vary? Do you know?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: It can vary. It's more likely if you get diagnosed with it when you're a kid, it's genetic, if it's somebody else in your family has it. But it can develop at any age. I was in my mid-30s, and came out of nowhere, so.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. And you mentioned how this is a part of people's entire life. Do you ever talk to people who feel that they've been judged or have lost out on opportunities? I mean, what are some of the real-life experiences you or others have struggled with?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Well, I feel pretty fortunate to live in this day and age and in the country that I do, because still, even now in some countries, if you have it, you are not allowed to get married. You're not allowed to reproduce. You're kind of shunned from public. Even your family members, if they don't have it.

So just the fact that here, there's more acceptance being gained as more funding is being put towards research and the word out there. Yeah.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. Remind us how people can see your work or access it. Like, do you take it to different places and display it to get the word out, or how is it going to work?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Yeah. So I already have a line up of more people who are ready for the next session. And another event with the big, large portraits will be in the works. My Instagram is my full name, Sharolyn_Hagen_Photo, and also, my website, sbhphotography.com.

NINA MOINI: You mentioned the support group that you're a part of, and that's just great that, that exists. It's more grassroots or kind of organically driven, it seems. Tell us, if you would, just what are the resources beyond that? Are there a lot of resources beyond that, or is it kind of people within the community helping one another out?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Even within the past 10 years, it's changed quite a bit. There's The Global Vitiligo Foundation that does an annual conference, and it can be hundreds of people who come together for one weekend. And it's around World Vitiligo Day, which is June 25.

NINA MOINI: And did you go to that/

SHAROLYN HAGEN: I have been to the one. They had it in Minneapolis in 2022.

NINA MOINI: Cool.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: And I hope to get to the next one, as well. And that, just being surrounded with a room full of people that all have it, is just, I can't even explain how safe and great it feels to know that people understand.

NINA MOINI: And you mentioned that sometimes people could be reluctant in the beginning to allow you to photograph them. But I do wonder, too, what it's like for them to see the images? And if there's a special way that you like to reveal that, or if some-- and then, what is the reaction, and how does that make you feel?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Yeah. So originally when I take them, we do like a handful of the best shots for people to help narrow down which ones we want to print for the series. And I'll never forget, one of the women showed up at a event that we had where it was-- it's a big 24 by 36 inch print. And she stood there, and she just put her hand over her mouth, and she got teary. And she was like, "I never like photos of myself, and this makes me feel beautiful." And that just, like-- that's the whole reason. Yeah.

NINA MOINI: Wow. That is beautiful. And have you thought about ways to bring your work to greater audiences? What do you think about? What would be next for showcasing this work on more platforms?

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Yeah. So, a dream job would be to just to travel the world and photograph people with vitiligo.

NINA MOINI: Oh, that would be cool.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: I was flown to Orlando, Florida, this spring to go to a dermatologist symposium, where there was about 125 people all from around the world that are studying vitiligo. And I was able to speak as a patient advocate and talk to-- of course, there are some people in big pharma that were there that mentioned that there's opportunities for grants and things like that. So I'm looking into--

NINA MOINI: Well--

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Maybe.

NINA MOINI: --just thinking about expanding and bringing your work to more people.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Exactly.

NINA MOINI: Beautiful work. Thank you so very much for coming by Minnesota Now. Thank you for coming in the studio and sharing it with us. I really appreciate it.

SHAROLYN HAGEN: Thanks for helping spread awareness.

NINA MOINI: Thank you, Sharolyn. That was photographer Sharolyn Hagen. You can see again the photographs of Sharolyn and the others with vitiligo. Head to our website, mprnews.org. We'll have her information there.

Download transcript (PDF)

Transcription services provided by 3Play Media.