The history of the farm crisis that inspired the creation of Farm Aid

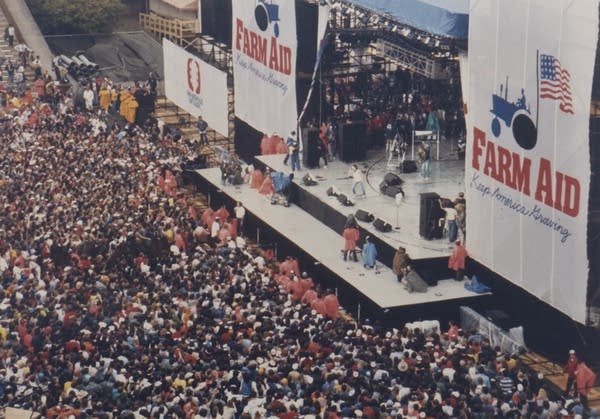

The first Farm Aid took place September 22, 1985, at Memorial Stadium on the University of Illinois campus in Champaign, Ill.

John Graham/courtesy Champaign County History MuseumGo Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Audio transcript

NINA MOINI: Well, this Saturday, the 40th annual Farm Aid Concert will take place at Huntington Bank Stadium in Minneapolis. It will feature artists that kicked off the original Farm Aid concert back in 1985, including Willie Nelson, Neil Young, and John Mellencamp.

The concert fundraiser was a response to an economic crisis farmers faced across the US during that time. The agricultural financial struggle of that period hit Minnesota's workers hard. Here to explain the history of that period in time and how it's changed farming today is University of Minnesota Applied Economics Professor Marc Bellemare. Thanks for being here in the studio with me, Marc.

MARC BELLEMARE: Thank you for having me.

NINA MOINI: I love that this is a fun concert. And we're bringing the history angle to it here on Minnesota Now because it's really important, right? Because so many of the struggles that people were facing then, there might be different reasons now, but the struggles end up looking the same in terms of what people have to deal with, it seems. So I wonder if you could take us back to, say, the early 1970s, where things were going well, and then something happened, right?

MARC BELLEMARE: Yeah. So what happened is that-- and I like that you wanted to go back to the early '70s because the genesis of the farm crisis of the 1980s was the OPEC oil crisis of 1973, which drove the energy prices way up. And what that did is all those commodities co-moved together. The prices of all those commodities co-moved together.

And as energy prices started going up, the price of all commodities, including the stuff that we grow on lands in the Midwest in the United States also went up. And so for a good long while after 1973, prices were-- it was kind of like the Roaring '70s in terms of agriculture.

NINA MOINI: Sure.

MARC BELLEMARE: And farmers were encouraged to take on more debt than they should. The value of land was-- price capitalizes all expectations about the future worth something. So the value of land was going up. And people were buying land, and they were taking loans. Interest rates were low. And then what happened is what we call a cost price squeeze, where eventually prices went down very rapidly, and people had over-borrowed.

And so the prices that they ended up getting-- oftentimes, prices fell by 50%. The prices that farmers ended up getting were well below what it cost them to produce one unit of production, one unit of crop or one unit of output. And so what that means is that they were making negative profit, right? And so you can't sustain that for very long. And what we ended up seeing was farmers exiting the agricultural sector, selling their land, selling equipment. And eventually, we saw way fewer farms in Minnesota and throughout the Midwest than there were at the beginning of the farm crisis.

NINA MOINI: Yeah, that is so tough, because when I talk to people who are maybe fifth or sixth-generation farmers, and they say it's really hard to get this business to keep going as a family and for people not to go in a different direction. So to know that during that time, there were probably many farms that went away and many family farms that went away, which is really tough because it does matter, right, to the economy when farms consolidate, and we don't have as many of these family farms. How does that impact us all?

MARC BELLEMARE: Yeah, let me just give you some figures. So in 1978, there were about 100,000 farms in Minnesota. Nowadays, as of 2015, which is the most recent number that I know of, it's about 75,000. But between the start and the end of the farm crisis, it went from 100,000 to about 85,000.

And that does change the landscape certainly, right? It means that there are fewer owners of those farms. And there are fewer total farms, even though the average size of your typical farm goes up. Part of that, though, is that it's not just the farm crisis. The farm crisis certainly has precipitated that movement, but a lot of it has been occurring throughout the 20th century and the early 21st century in the form of greater mechanization and greater technological upgrading, which means that you have to make fixed investments in order to gain access to buy or at least lease all that equipment that is now necessary to be as productive as the next guy or girl.

And what that means is that it doesn't make sense for a small-scale operation to make those investments. And so we see what we call in economics increasing returns to scale. And the presence of increasing returns to scale in agriculture in high-income countries like ours means that we are seeing a de facto kind of consolidation and fewer and fewer farms. And so while the farm crisis certainly has precipitated that or made it faster at that time than it should have been, this is something that had been ongoing. And this is something that kept going because of greater mechanization, and it still keeps on going.

And so, I completely understand the feeling that it certainly is extremely sad when we see those communities getting hollowed out because we need less labor. And therefore, people don't have to stick around the countryside to work on farms. And communities become frayed because there are fewer people around. And really, what maintains a community are those relationships between people. Unfortunately, it's really the nature of technological progress that drives us to that point. And if we want a farm sector that is competitive with the rest of the world, they have to use that kind of technology in order to remain competitive.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. And I love that you mentioned community and how important it is. Because if there aren't people around to see the struggle that's going on, that's how it could be hidden. So I think efforts like Farm Aid are a way to, even if it's for a day, bring all this global awareness.

I wonder if you could tell a little bit about why that was the idea in 1985, which it's so funny when people say 40 years ago was 1985. I still think it was 1960. I don't know why. I'm sure people listening can relate. But yeah, 40 years ago, 1985, how did Farm Aid and the concert and that kind of movement come to be?

MARC BELLEMARE: Yeah, you and I both, Nina, because in 1985, I was the age that my daughter is currently.

NINA MOINI: And I was not alive, so.

MARC BELLEMARE: Right. And so what happened is, in 1985, we were in the wake of the farm crisis, or we were slowly coming out of it. And there was also a famine in Ethiopia at the time. You may not remember that because you said you were not alive at the time. But I do remember seeing on television those ads for raising money for Ethiopian children who were starving. There was famine in Ethiopia.

And so there was this concert called Live Aid. And I think, if I recall correctly, that it was Sir Bob Geldof, who had convened Live Aid. And at Live Aid, Bob Dylan made kind of an offhand remark where he said, wouldn't it be nice if some of the money that we raise here could go to American farmers who are also suffering? And then Willie Nelson, Neil Young, I think, and John Cougar Mellencamp all kind of got together and decided to do something similar to Live Aid, but for the American farmer, which is Farm Aid.

And the first Farm Aid concert was held in Urbana Champaign, where the University of Illinois is located. I think there were about 80,000 people who were there. There were a number of artists. And one of the things-- so this is an interesting interview because it combines two of my passions, which is the agricultural economy and music.

NINA MOINI: Aw.

MARC BELLEMARE: That was the first time that Sammy Hagar performed with Van Halen after David Lee Roth left the band--

NINA MOINI: Oh, wow.

MARC BELLEMARE: --and Sammy Hagar was recruited by Van Halen. So there was a huge roster--

NINA MOINI: Momentous.

MARC BELLEMARE: --of artists.

NINA MOINI: Yeah.

MARC BELLEMARE: And what it did is that at the end of the day, it didn't raise all that much money. It raised about $9 million, which I don't mean to sound callous by saying $9 million is not a lot. I would certainly would love to have $9 million, especially that $9 million in 1985 is now worth about 25.

NINA MOINI: Right. [LAUGHS] Sure.

MARC BELLEMARE: But when you divide it by the total number of farms at the time, it's not that much. And I did a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation before coming on the air. I think if I use that as denominator, the number of farms in Minnesota at the time-- this is just in Minnesota, this $9 million for all farms, and we're looking just at our state-- it would be about $120 per farm--

NINA MOINI: Oh, wow.

MARC BELLEMARE: --which is not a whole lot. They needed a whole lot more than $120 to pay the debts that they had incurred during the farm crisis.

NINA MOINI: Right.

MARC BELLEMARE: And so what it did, I think, more than anything, is that it started this movement of Farm Aid. So there have been Farm Aid concerts roughly every year since 1985. As you said, the 40th is coming this weekend at Huntington Bank Stadium at University of Minnesota, my employer.

But it helped raise awareness of people because as-- and coming full circle with the story I was telling you about technological progress and fewer and fewer people working in rural areas and working in agriculture, we are getting, by the day, almost, further and further removed from where primary commodities, mainly our food, but also the textiles we wear and some of the fuel that we use, if we use ethanol, are all coming from. It's kind of this nebulous thing where we go to the grocery store, we buy stuff, we eat it, but we don't really spend a whole lot of time thinking about--

NINA MOINI: Where does it come from?

MARC BELLEMARE: --where does it come from, who grows it, what are their conditions, and so on.

NINA MOINI: Right. So I love what you're saying. It wasn't even necessarily the dollar amount, although, of course, that's helpful. It's about raising awareness and really taking a moment to think, where does our food come from and who are the people, the human beings behind it, and showing appreciation there. I think that's what it's about for all of these 40 years. So thank you very much for stopping by, Marc, and telling us about the economic history of it all. I've loved it. Thank you.

MARC BELLEMARE: Thank you, Nina.

NINA MOINI: That was Marc Bellemare, an applied economics professor at the University of Minnesota.

The concert fundraiser was a response to an economic crisis farmers faced across the US during that time. The agricultural financial struggle of that period hit Minnesota's workers hard. Here to explain the history of that period in time and how it's changed farming today is University of Minnesota Applied Economics Professor Marc Bellemare. Thanks for being here in the studio with me, Marc.

MARC BELLEMARE: Thank you for having me.

NINA MOINI: I love that this is a fun concert. And we're bringing the history angle to it here on Minnesota Now because it's really important, right? Because so many of the struggles that people were facing then, there might be different reasons now, but the struggles end up looking the same in terms of what people have to deal with, it seems. So I wonder if you could take us back to, say, the early 1970s, where things were going well, and then something happened, right?

MARC BELLEMARE: Yeah. So what happened is that-- and I like that you wanted to go back to the early '70s because the genesis of the farm crisis of the 1980s was the OPEC oil crisis of 1973, which drove the energy prices way up. And what that did is all those commodities co-moved together. The prices of all those commodities co-moved together.

And as energy prices started going up, the price of all commodities, including the stuff that we grow on lands in the Midwest in the United States also went up. And so for a good long while after 1973, prices were-- it was kind of like the Roaring '70s in terms of agriculture.

NINA MOINI: Sure.

MARC BELLEMARE: And farmers were encouraged to take on more debt than they should. The value of land was-- price capitalizes all expectations about the future worth something. So the value of land was going up. And people were buying land, and they were taking loans. Interest rates were low. And then what happened is what we call a cost price squeeze, where eventually prices went down very rapidly, and people had over-borrowed.

And so the prices that they ended up getting-- oftentimes, prices fell by 50%. The prices that farmers ended up getting were well below what it cost them to produce one unit of production, one unit of crop or one unit of output. And so what that means is that they were making negative profit, right? And so you can't sustain that for very long. And what we ended up seeing was farmers exiting the agricultural sector, selling their land, selling equipment. And eventually, we saw way fewer farms in Minnesota and throughout the Midwest than there were at the beginning of the farm crisis.

NINA MOINI: Yeah, that is so tough, because when I talk to people who are maybe fifth or sixth-generation farmers, and they say it's really hard to get this business to keep going as a family and for people not to go in a different direction. So to know that during that time, there were probably many farms that went away and many family farms that went away, which is really tough because it does matter, right, to the economy when farms consolidate, and we don't have as many of these family farms. How does that impact us all?

MARC BELLEMARE: Yeah, let me just give you some figures. So in 1978, there were about 100,000 farms in Minnesota. Nowadays, as of 2015, which is the most recent number that I know of, it's about 75,000. But between the start and the end of the farm crisis, it went from 100,000 to about 85,000.

And that does change the landscape certainly, right? It means that there are fewer owners of those farms. And there are fewer total farms, even though the average size of your typical farm goes up. Part of that, though, is that it's not just the farm crisis. The farm crisis certainly has precipitated that movement, but a lot of it has been occurring throughout the 20th century and the early 21st century in the form of greater mechanization and greater technological upgrading, which means that you have to make fixed investments in order to gain access to buy or at least lease all that equipment that is now necessary to be as productive as the next guy or girl.

And what that means is that it doesn't make sense for a small-scale operation to make those investments. And so we see what we call in economics increasing returns to scale. And the presence of increasing returns to scale in agriculture in high-income countries like ours means that we are seeing a de facto kind of consolidation and fewer and fewer farms. And so while the farm crisis certainly has precipitated that or made it faster at that time than it should have been, this is something that had been ongoing. And this is something that kept going because of greater mechanization, and it still keeps on going.

And so, I completely understand the feeling that it certainly is extremely sad when we see those communities getting hollowed out because we need less labor. And therefore, people don't have to stick around the countryside to work on farms. And communities become frayed because there are fewer people around. And really, what maintains a community are those relationships between people. Unfortunately, it's really the nature of technological progress that drives us to that point. And if we want a farm sector that is competitive with the rest of the world, they have to use that kind of technology in order to remain competitive.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. And I love that you mentioned community and how important it is. Because if there aren't people around to see the struggle that's going on, that's how it could be hidden. So I think efforts like Farm Aid are a way to, even if it's for a day, bring all this global awareness.

I wonder if you could tell a little bit about why that was the idea in 1985, which it's so funny when people say 40 years ago was 1985. I still think it was 1960. I don't know why. I'm sure people listening can relate. But yeah, 40 years ago, 1985, how did Farm Aid and the concert and that kind of movement come to be?

MARC BELLEMARE: Yeah, you and I both, Nina, because in 1985, I was the age that my daughter is currently.

NINA MOINI: And I was not alive, so.

MARC BELLEMARE: Right. And so what happened is, in 1985, we were in the wake of the farm crisis, or we were slowly coming out of it. And there was also a famine in Ethiopia at the time. You may not remember that because you said you were not alive at the time. But I do remember seeing on television those ads for raising money for Ethiopian children who were starving. There was famine in Ethiopia.

And so there was this concert called Live Aid. And I think, if I recall correctly, that it was Sir Bob Geldof, who had convened Live Aid. And at Live Aid, Bob Dylan made kind of an offhand remark where he said, wouldn't it be nice if some of the money that we raise here could go to American farmers who are also suffering? And then Willie Nelson, Neil Young, I think, and John Cougar Mellencamp all kind of got together and decided to do something similar to Live Aid, but for the American farmer, which is Farm Aid.

And the first Farm Aid concert was held in Urbana Champaign, where the University of Illinois is located. I think there were about 80,000 people who were there. There were a number of artists. And one of the things-- so this is an interesting interview because it combines two of my passions, which is the agricultural economy and music.

NINA MOINI: Aw.

MARC BELLEMARE: That was the first time that Sammy Hagar performed with Van Halen after David Lee Roth left the band--

NINA MOINI: Oh, wow.

MARC BELLEMARE: --and Sammy Hagar was recruited by Van Halen. So there was a huge roster--

NINA MOINI: Momentous.

MARC BELLEMARE: --of artists.

NINA MOINI: Yeah.

MARC BELLEMARE: And what it did is that at the end of the day, it didn't raise all that much money. It raised about $9 million, which I don't mean to sound callous by saying $9 million is not a lot. I would certainly would love to have $9 million, especially that $9 million in 1985 is now worth about 25.

NINA MOINI: Right. [LAUGHS] Sure.

MARC BELLEMARE: But when you divide it by the total number of farms at the time, it's not that much. And I did a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation before coming on the air. I think if I use that as denominator, the number of farms in Minnesota at the time-- this is just in Minnesota, this $9 million for all farms, and we're looking just at our state-- it would be about $120 per farm--

NINA MOINI: Oh, wow.

MARC BELLEMARE: --which is not a whole lot. They needed a whole lot more than $120 to pay the debts that they had incurred during the farm crisis.

NINA MOINI: Right.

MARC BELLEMARE: And so what it did, I think, more than anything, is that it started this movement of Farm Aid. So there have been Farm Aid concerts roughly every year since 1985. As you said, the 40th is coming this weekend at Huntington Bank Stadium at University of Minnesota, my employer.

But it helped raise awareness of people because as-- and coming full circle with the story I was telling you about technological progress and fewer and fewer people working in rural areas and working in agriculture, we are getting, by the day, almost, further and further removed from where primary commodities, mainly our food, but also the textiles we wear and some of the fuel that we use, if we use ethanol, are all coming from. It's kind of this nebulous thing where we go to the grocery store, we buy stuff, we eat it, but we don't really spend a whole lot of time thinking about--

NINA MOINI: Where does it come from?

MARC BELLEMARE: --where does it come from, who grows it, what are their conditions, and so on.

NINA MOINI: Right. So I love what you're saying. It wasn't even necessarily the dollar amount, although, of course, that's helpful. It's about raising awareness and really taking a moment to think, where does our food come from and who are the people, the human beings behind it, and showing appreciation there. I think that's what it's about for all of these 40 years. So thank you very much for stopping by, Marc, and telling us about the economic history of it all. I've loved it. Thank you.

MARC BELLEMARE: Thank you, Nina.

NINA MOINI: That was Marc Bellemare, an applied economics professor at the University of Minnesota.

Download transcript (PDF)

Transcription services provided by 3Play Media.