Publication gives new life to history of black community in the Twin Cities

Like this?

Log in to share your opinion with MPR News and add it to your profile.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

It's a secret history that, for some, wasn't so secret.

Well-worn copies of Walter Scott's books dating back to 1956 were shelved in personal libraries and laid on coffee tables all over Minneapolis.

"Dad always said what he wanted to do was put together a pictoral resume of the Black community, so that the world really could see the accomplishments, the goals, kind of the other side of day to day life," said Anthony Scott, son of publisher Walter Scott.

The one-time telephone company security guard became one of the premier historians of the Twin Cities black community.

Support the News you Need

Gifts from individuals keep MPR News accessible to all - free of paywalls and barriers.

His collection has now been republished by the Minnesota Historical Society and his children are hoping to carry on his work.

"I get calls from all over the country, 'how did your dad do this? How did he put it all together?' And when I look at it from the perspective of doing a new book, my sister and I, my brothers, say this is not going to be an easy task. But we're gung-ho to make it happen," Scott said.

Walter Scott was born in Greenville, Mississippi in 1929, grew up in Chicago and made his way to Minneapolis in 1949. He liked what he found when he got here — so much so that he decided to write a book about it.

"Our aim here at the Beacon is to publish the achievements made by Negroes locally," he wrote in the "Dear Reader" letter in his first book, the "Centennial Edition of the Minneapolis Beacon," published in 1956. It was also the first ever edition. "They are, admission to any school at the state university, buying the home we can pay for, that is for sale on the open market, getting more jobs that we are qualified to do, and the joy from the assurance that we too can go to the top of local industry, only to be conspicuous by God's action and not by the pigmentation of our skin."

It may have been more ambition than reality at the time.

But it sparked a decades-long endeavor, practically single-handed, to record and celebrate black Minnesota. Scott stitched the account together with photos and captions, brief historical summaries and letters of appreciation. He literally cut and pasted the galley proofs together by hand at home, first while working full time at Northwestern Bell, then for the Metropolitan Airports Commission. He self-published a second edition, the "Minneapolis Negro Profile" in 1968. Then came "Minnesota's Black Community" in 1976. He put out smaller, magazine-sized periodicals as well.

Activist and former St. Paul NAACP vice president Yusef Mgeni showed up in the 1976 edition. He says the books cataloged African-Americans active in civil rights, business, journalism, religion and other affairs.

"And so you had one repository, literally the only one that captured people in leadership positions in all of those fields and more," Mgeni remembers. "They were distributed hand to hand, people put out the word. The African-American newspapers featured them, featured excerpts from them, and Walter was a tireless champion of the work. Everywhere he went, he had an armful and he sold them all before he left. They were coffee table books and points of pride."

But it wasn't just a who's who.

The books included photos of teachers in classrooms, Bill Dye running a paint gun in a generator factory, dressmaker Ruth McQuerry modeling her work, Sears clerks, Dayton's and General Mills executives, meter readers, bank tellers, pastors, tailors and pilots. There are models, and Vikings and Twins players. There are portraits of barber shops, realty offices and even just homes with beautifully landscaped lawns. The books focus on work and family and local boys and girls made good, distilled to meticulous detail.

"And as the books progressed, from 1956 through the '70s, you could see the progression of the community," said Anthony Scott, who remembers helping sell his father's work. "You could see people doing different types of jobs, I mean, superintendents of schools, attorneys, doctors."

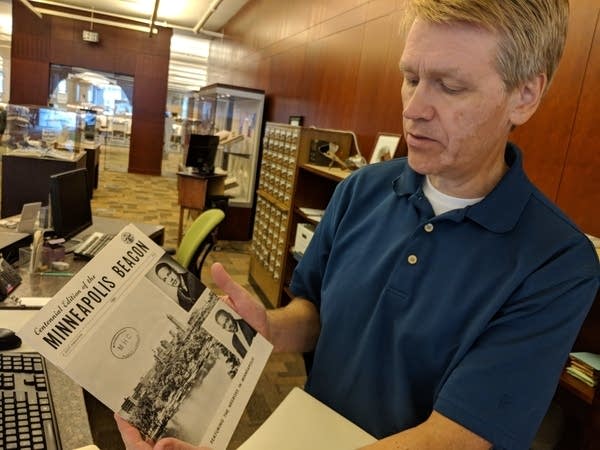

Ted Hathaway is the manager of the county and city history collection at the downtown Minneapolis Hennepin County Library — where they have Scott's original publications. He says they've always been a touchstone, albeit an obscure one, of local African-American history.

"It was an effort for people to recognize that, yes, we are an important community," Hathaway said. "(To say) we have made a lot of important contributions. And these aren't showing up in the newspaper. These aren't showing up in the usual sources. So, I have to go out and do this. Somebody's got to do this."

Scott died in 2001. But now Scott's son, and daughter, Chaunda, have taken up the task. They brought the books to the historical society, and they've been newly printed together as "The Scott Collection."

And in tribute to their father's work, the brother and sister are working on a fourth version, titled "Minnesota's Black Community, the 21st Century." Chaunda Scott lives in Michigan now, but travels back to work on it. They've put together a Facebook page to help promote and joined forces with the Hennepin County Library to get the word out.

"We looked at how my Dad put this together ... we go around to different community organizations and libraries and whatnot. And then we hold photo shoots. We're chronicling them by professions, you know, beauty and fashion, fine arts. STEM fields, sports, education," Scott said.

She says people still remember seeing their family and friends in the books, even though they've been out of print for decades.

Replicating the effort is a tough go, Scott said. The Black community now is much bigger, less geographically concentrated and much more diverse. She says there's no hope of getting as full a reflection of the culture as their father got, although they also have the advantage of computer technology, digital photography, cloud storage and publication tools that make some parts of the job more practical.

They hope to have a new edition done in February.