Dreamland: Then and now

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

In the late 1940s, Anthony Brutus Cassius was the first Black man to obtain a liquor license in the city of Minneapolis. He went on to create safe social spaces, specifically bars, for Black people for 47 consecutive years.

After producing a radio documentary about his life in 2021, I found myself wondering, what is his legacy? Would Cassius be satisfied if he were alive today?

For decades, the Dreamland Café in South Minneapolis was often the place to be if you were Black and wanted to socialize. When Nat King Cole came to town in the 1940s, he played the Dreamland.

In many ways, the Dreamland grew out of Cassius’s experiences growing up.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Cassius was just 13 when he arrived in Minnesota in 1922. He came from Oklahoma, put on a train by his father just months after the Tulsa Race Massacre destroyed much of the city's vibrant and prosperous Black community, known to many as ‘Black Wall Street.’

On his first night in St. Paul, he got a porter job at the Merchant Hotel at the top of Kellogg Hill and slept on a mattress in the basement. That would remain his home until he graduated from Central High School.

In his 70s, Cassius recorded an oral history for the Minnesota Historical Society, looking back at his life and accomplishments. He described his impressions of the Twin Cities when he first arrived:

“This was a prejudiced town, St. Paul-Minneapolis.” His voice sounds strong and angry. “Back then the only thing you could do was go to school. There was no prejudice in the school system. Because there wasn't enough [of us] to constitute a threat. The class I graduated in was 1,200, and there were only two or three colored in the whole school.”

Because few job opportunities were open to Black men at the time, Cassius went on to wait tables in hotels. This was even though he graduated from college as a top athlete and student at a time when having a college degree was a rarity for Black men. But he soon ran into extreme racial inequities in that industry. So he went and formed the first all-Black waiters union in Minneapolis.

Eventually, he began working for his liquor license. It took two years. “But through persistence, I got it,” he said in the oral history.

Over 47 consecutive years, he owned three bars. They were known as some of the first, and most consistent, integrated spaces in Minneapolis.

But Cassius opened these bars for a specific reason. He wanted to give Black people a place to be, to socialize, to conspire and to dream. Finding safe space for Black people to gather was a precious commodity in 1940s and ‘50s America.

In the oral history, Cassius spoke about forming the Minnesota Club, a group of civil rights activists who organized to protest the screening of D.W. Griffiths’ now notorious “The Birth of A Nation” in downtown Minneapolis, among many other movements.

“There were about eight of us,” he explained in the history. We met once a month in Fosters Sweet Shoppe on 6th and Lyndale. We met in the back. And all they wanted us to do if we met there was to buy a dish of ice cream.”

At the end of the quote, you can hear him emit a gasp of incredulous laughter, as though the thought of being allowed to gather over a dish of ice cream was still a bit amazing to him.

The shell of the old Dreamland Café, Cassius’ first bar, still stands on 38th street in the old southside of Minneapolis. Once a thriving Black community, cars noisily speed by the dilapidated intersection. But there’s a new dream unfolding for the space, and like Cassius’ original vision, it's a dream with a purpose.

Anthony Taylor is the community development lead of the Cultural Wellness Center. It’s a Minneapolis-based social justice organization with a mission to support the idea that active living and green space are crucial to the wellbeing of Black people. His organization wants to bring back the old Dreamland space, in a true evolution of Cassius’ vision.

“‘Dreamland on 38th’ is actually a revitalization of this entire community, as an African American legacy community,” he explained. “Fortunately, or unfortunately, the murder of George Floyd anchored that for us. We are now three blocks from there. So what we see is a connection between this development, what will emerge at 38th and Chicago, and we really see it as a destination for human rights and social justice fighters from all over the world.”

The vision for the project is ultimately a place to eat and drink. But the fact Taylor is imagining Dreamland as a destination for international social justice fighters, punctuates the importance of such spaces.

“We're saying ‘social’ right now, but in my head I substitute ‘safe,’” he said. “Creating spaces that the community knows are safe for them to be themselves that are anchored in their own renewal, regeneration and socialization, that is really the conscious development of a safe space. And really, there's a challenge around that for Black people. There's still a challenge for that.”

Several recent mass shootings have been identified as racially motivated hate crimes, including the May 14 killing of 10 Black people in Buffalo, New York. Safe spaces for Black people seem as crucial as they’ve ever been.

“I think what people don't realize is there is an energetic cost of being Black in white dominated spaces all the time,” Taylor emphasized.

If we can agree that these spaces are crucial, how, really, are we doing in the city of Minneapolis? I posed the question to other Black owners and operators of social spaces, as well as some patrons.

There is a new generation of Black-owned space in Minneapolis, and with them comes a new outlook and sensibility, too.

Gene Sanguma is part of a collective of 20-something best friends who came together over a common bond: having a good time. But not any old kind of good time. A safe good time.

On a recent sunny spring day in the middle of downtown Minneapolis, sitting on the third floor patio at Ties Lounge and Rooftop, their new downtown Minneapolis nightclub, he recalled the energy that went into its creation.

“We [thought we could] provide fun, and safety. We said, ‘Let's do it. Let's come up with something.’”

“Something” ended up being the multi-story venue on the Nicollet Mall in the heart of downtown Minneapolis. You can eat, you can drink and you can dance. But you can also grab a quiet table with friends and talk into the night. It’s like an anti-nightclub that still manages to operate with nightlife and good times at the forefront.

“Ties is a community,” he went on. “We wanted to make it so it doesn't matter where you come from, what aspirations you may have in your life — you come into Ties, you feel welcomed. We wanted to provide a safe space for all people to come together and just enjoy themselves and network. We felt like the city really, really needed it.”

Ties feels like an echo of what Cassius wanted to build.

Dreamland on 38th’s Anthony Taylor realized this about Cassius’ mission, too.

“When young Black people are allowed to congregate, they start to look outward and organize themselves,” he told me. “When you’re creating spaces where Black people feel emotionally safe, you can imagine a future that includes you.”

The exclusion of Black people from public spaces is part of America’s fabric. As Taylor put it, Black people are afraid of public space. Because when it goes wrong? It goes really wrong. “It’s not a skinned knee,” he said.

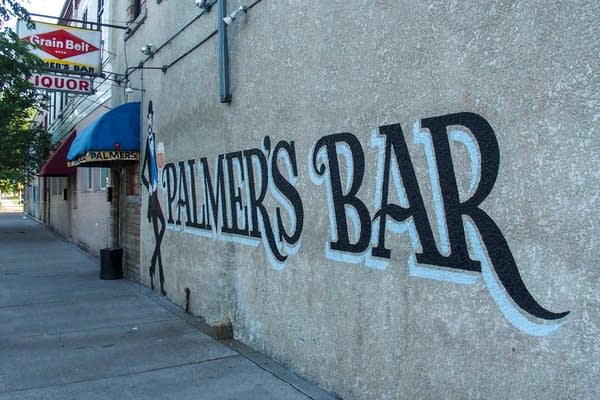

As a young person, I gravitated to Palmer’s Bar on the West Bank of Minneapolis. Though the dive bar institution has a rough and tumble façade and reputation, I immediately found that it was one of the most welcoming spaces I had ever been to.

Tony Zaccardi has owned Palmer’s for four years, but he says it's long attracted a seriously diverse mix of customers.

“I always tell people, my motto of what Palmer's is, it's Black, white, gay, straight, trans, left, right, rich, poor. So on and so forth,” he said. Then he added “Everyone is welcome until you're an a-hole.”

But there’s something else about Zaccardi. He’s a Black man, and his ownership adds another layer of meaning to the already storied place. I put the question to him: would Cassius be satisfied if he were alive today?

“I think he'd be disappointed as hell at Black bar ownership and Black representation in bars. Restaurants are a little better, but it's still not at all where it could or should be. But I think he'd be proud of me. I just started tearing up when I said that. I think he’d be proud of me.”

I think Cassius would be proud of Tony too. I’m proud of Tony. But this is a story about whether or not Cassius would be proud of the Twin Cities.

I happened to catch Wain McFarlane, longtime fixture of the Twin Cities music scene and frontman of internationally known reggae-rock band, “Ipso Facto,” on the patio of Palmer’s, where he’s a regular. He didn’t think Cassius would be satisfied, either.

“I'd say we still haven't made the progress. It’s still controlled by another entity,” he told me from a table he’s sharing with his son. “But at least Tony (Zaccardi) finally owns something.”

McFarlane mentioned how difficult it is to get a foothold into the business, and he believes it’s time for something to change.

“I think we need some sort of financial institution to allow us to have our dream and help us manage it. You know, we don't want to waste the money,” he said.

I approached a group of other Black patrons on the patio. Zaccardi said one of them is in every day. I asked what it is about Palmer’s that makes them feel safe, and what keeps them coming back.

A guy with long braids named Caezar told me, “A cat can hang out with a dog here. Nobody would pay attention to it. It’s like everybody’s welcome. We’re all family. For real. We love each other.”

At the same table, a woman named Keisha agreed. “When you come here it’s so comfortable and laid back. It's just very peaceful. I've been to other bars, but at Palmer’s we have fun. We have a ball.”

Black people feeling comfortable, laid back, peaceful and having a ball? It’s a much taller order than it should be in America, as Cassius attested to all those years ago.

There’s an energetic cost to getting there, as Anthony Taylor so eloquently put it. We’re not there yet.

These things run deep. Tony Zaccardi tells a story of hanging out at Mortimers, another south Minneapolis institution, chatting with the owner, and a friend.

“Somebody walked in wearing a Palmer’s Bar T-shirt,” he remembered. “And she said, ‘Palmers! I haven’t been there in years, but I heard a brother owns it.’ And [the owner said] ‘Yeah, the guy standing right next to you, he’s the guy that owns it.’ And she started bawling. And then I started bawling. And I was like, ‘OK, this is actually something that's pretty special.’ It was astonishing. It really touched my heart and I realized why it's so important to a lot of people.”

It’s so important to a lot of people because still, in 2022, Black people cannot take safe social space for granted. Places like Palmer’s, and people like Tony Zaccardi, are providing a service that goes far beyond pouring a drink. And Cassius would be proud — some 80 years after opening the Dreamland Bar & Café, these spaces are his legacy.

But I think he would be prouder if we were able to drop the word “safe” from social space.

Pass the MicDear reader,

Your voice matters. And we want to hear it.

Will you help shape the future of Minnesota Public Radio by taking our short Listener Survey?

It only takes a few minutes, and your input helps us serve you better—whether it’s news, culture, or the conversations that matter most to Minnesotans.