Bill would set standard for preserving rape kits in Minnesota

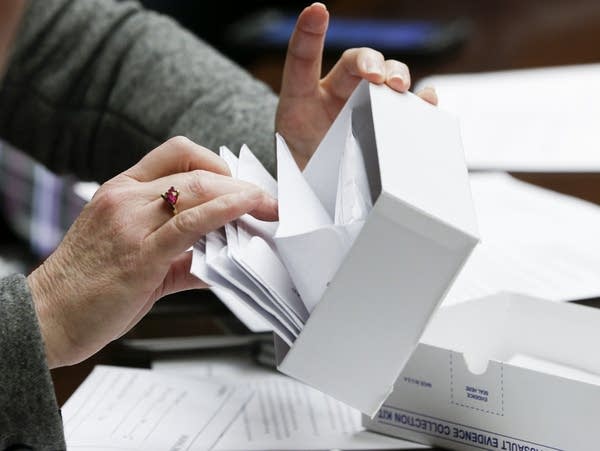

Rep. Marion O'Neill looks through a sexual assault evidence collection kit during testimony on work done by the Working Group on Untested Rape Kits, during the Feb. 27, 2018, meeting of the House Public Safety and Security Policy and Finance Committee.

Paul Battaglia | Minnesota House of RepresentativesGo Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.