Workplace protections still apply when you work from home

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Suppose you’re an employee working at home instead of the office. And you somehow get injured while on the clock.

Is that a home accident? Or a workplace injury?

Well, it’s an issue for your employer.

“Work injuries happen at home all the time. And if you get hurt while working at home, you're entitled to benefits under the Minnesota Workers Compensation Act,” said Gretchen Hall, a Twin Cities attorney specializing in workers’ compensation.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Hall said a crucial court ruling more than a decade ago established that an employee working at home is covered by workers’ compensation — even while taking a break from work.

If you suffer a work-related injury at home, you’re eligible to recover lost wages and medical costs and possibly qualify for rehabilitation services.

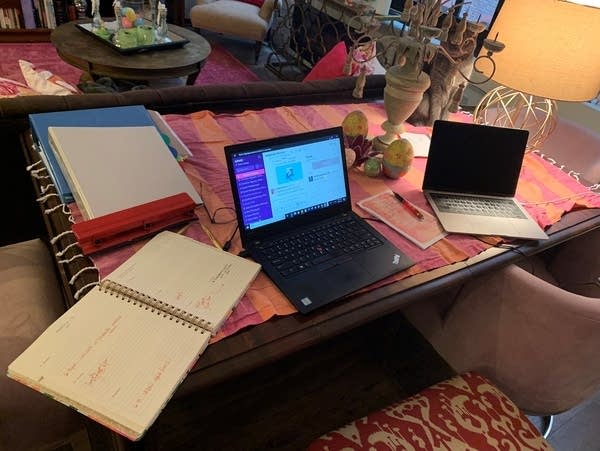

Hall said it would be prudent for employers to consider the ergonomic safety of workers laboring at home. Many may not have the stand-up desks, adjustable chairs and other ergonomic equipment they had at work to help ward off pain or injury.

There are many other ways employers must make sure a workplace is safe and accommodates employee needs.

For instance, the Americans with Disabilities Act applies to teleworkers, said attorney Susan Ellingstad, who heads the employment law department at the Lockridge Grindal Nauen law firm in Minneapolis. The ADA requires employers to provide reasonable changes to a workplace or job to enable employees with disabilities to do their jobs.

“Although working at home in of itself is an accommodation, there still could be accommodations necessary for disabled workers,” Ellingstad said. “Those obligations are still at play in terms of scheduling or different equipment.”

Technically, there are wage and hour and safety notices employers are obligated to post in workplaces. But Megan Anderson, an employment attorney at the Lathrop GPM law firm in Minneapolis, expects regulators won’t be looking for employers to put up bulletin boards in employees’ homes.

“I would hope that the regulators are going to give employers a little bit of grace, given the unique time,” she said.

Anderson said companies do have to pay attention to where employees are working. An organization may have to adhere to unique local regulations in communities where employees live — and now work. They might include local minimum wage ordinances, like those in Minneapolis and St. Paul, where a $15 minimum wage ordinance is being phased in over time.

Privacy is another key issue with telework.

Generally, employers can legally monitor employee activity on employer-provided computers, counting keystrokes, watching what’s displayed or stored on a computer and so on.

Companies typically warn employees that they should have no expectation of privacy on company computers. Mark Lanterman, chief technology officer of Computer Forensic Services, said that applies to employer-supplied laptops used at home. But he doubts most companies would stoop to spying on employees.

“I don't know of any significant employer here in Minnesota that is doing this. They're risking a severe hit to morale if they do deploy this type of tactic,” Lanterman, said.

Lanterman is a former member of the U.S. Secret Service Electronic Crimes Task Force. He said that while employer-owned machines can be used to monitor workers, employee-owned computers cannot — at least not without the permission of employees.

“If the company installs monitoring software on an employee-owned piece of hardware, that's a felony,” he said.

Lanterman suggests a quick low-tech method for detecting some surveillance software.

“Just putting a Post-it note over the camera is a good idea,” he said.

If you're asked to remove it, you know something’s up.